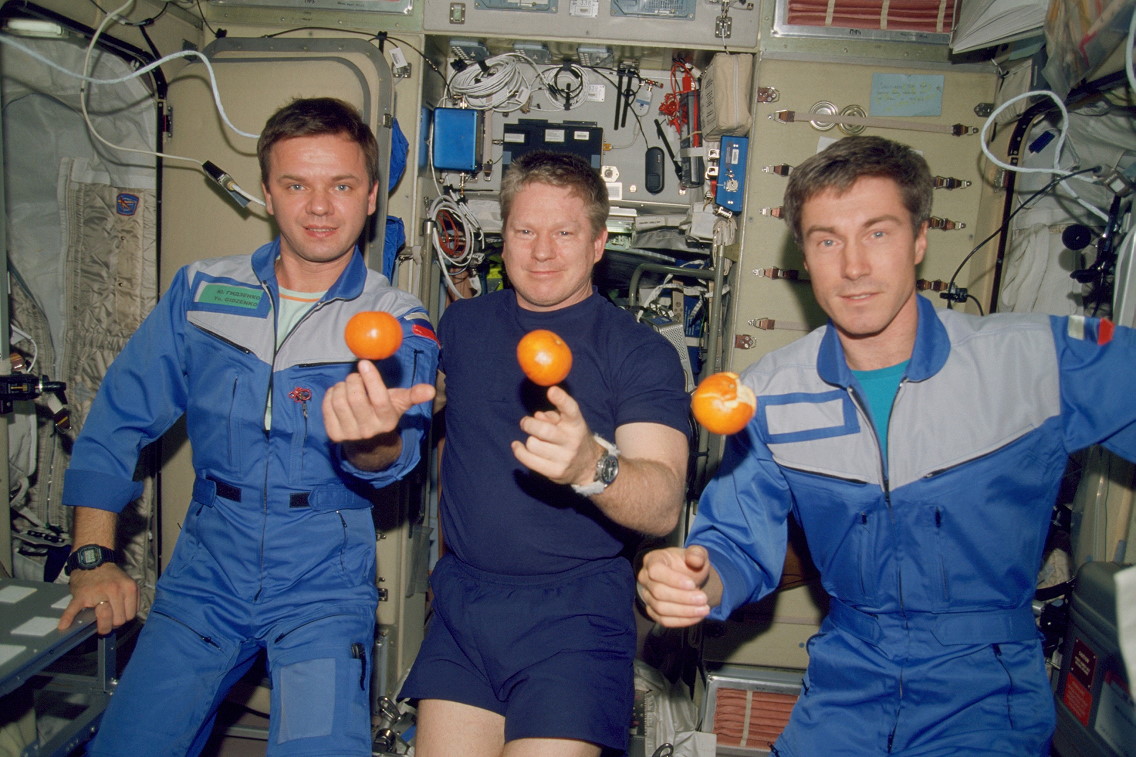

At 4:21 a.m. EDT in the present day (Thursday, 2 November), the Worldwide House Station (ISS)—which has to this point offered an off-Earth homestead for 269 people from 21 sovereign nations—handed its twenty third yr of steady habitation, extending proper again to the historic arrival of Expedition 1 Commander Invoice Shepherd and his Russian crewmates Yuri Gidzenko and Sergei Krikalev aboard Soyuz TM-31.

Launched on 31 October 2000, the three males had been coaching collectively for over 4 years and would spend 4.5 months overseeing maybe essentially the most essential part of ISS activation. Throughout their 136 days aboard the toddler house station, Shepherd, Gidzenko and Krikalev welcomed three House Shuttle crews as their planet-circling habitat progressively grew into the biggest inhabited construction ever positioned outdoors of Earth’s ambiance.

For Shepherd, his private {and professional} relationship with the ISS prolonged to a time far sooner than commanding its first long-duration increment. In June 1993, with three shuttle missions underneath his belt, he was named as NASA Assistant Deputy Administrator (Technical), primarily based on the company’s Washington, D.C., headquarters, with accountability for main the transition effort as House Station Freedom was rescoped and redesigned to change into the embryo of what grew to become the ISS.

Later that yr, Shepherd was named because the House Station Program Supervisor on the Johnson House Heart (JSC) in Houston, Texas, a place which he held for the subsequent two years. Remaining accessible to return to lively astronaut coaching, it appeared probably that Shepherd would draw an early ISS task and in January 1996 he and Krikalev had been named to Expedition 1, with launch initially focused aboard a Russian Soyuz spacecraft in the summertime of 1998.

Apparently, the third member of Expedition 1 went unannounced for a while, which Bryan Burrough, in his controversial e book, Dragonfly, attributed to the thorny query of whether or not a Russian or an American ought to command Expedition 1. Burrough instructed that veteran cosmonaut Anatoli Solovyov—who had commanded three earlier long-duration missions to Russia’s Mir house station—had been assigned to Expedition 1 however resigned his place when it grew to become clear that Shepherd would command.

“His resignation,” wrote Burrough, “capped months of behind-the-scenes maneuvering.” Regardless of the actuality, Yuri Gidzenko was assigned to Expedition 1 and by Could 1997 was deep into coaching with Shepherd and Krikalev, monitoring a launch in early 1999.

Sadly, delays within the arrival of Russia’s Zvezda service module—which offered essential crew quarters and life-support performance for the early expeditions—pushed its launch again from the autumn of 1998 to April 1999, earlier than it will definitely reached orbit in July 2000. This created a domino-like influence on shuttle meeting missions and the Expedition 1 crew discovered their very own launch pushed again to 31 October 2000.

“The day glided by actually quick,” Shepherd remembered in a NASA interview in 2010. “It was foggy, a form of dew on all of the home windows. I waved goodbye to my spouse, obtained on the bus, went right down to the Launch Meeting Space and we obtained our house fits on. Then, out of nowhere, my spouse got here up once we had been suited up and gave me an enormous hug, which was one thing you simply don’t do in our program.”

Upon arrival at Baikonur’s Website 1/5—the famed “Gagarin’s Begin”, from which Yuri Gagarin started his epochal voyage into house—they beheld the big Soyuz-U booster, topped by their Soyuz TM-31 spacecraft, and 400 well-wishers. To Shepherd, it couldn’t have contrasted extra markedly from his shuttle profession. “This can be a couple of million kilos of rocket, all able to go fly in house, all sitting there steaming and smoking, and we obtained 400 individuals, proper there,” he mentioned, incredulously.

With Gidzenko within the middle commander’s seat, Krikalev within the left-side “Flight Engineer-1” place and Shepherd within the right-side “Flight Engineer-2” place, the primary long-duration crew of the ISS started their mission at 12:53 p.m. native time (2:53 a.m. EDT. “The primary thought I had was now it’s beginning,” mentioned Krikalev later. “That is our first work and, oftentimes, it’s the best way you begin is the way it’s going to go subsequent.”

As they ascended, tv photos of Shepherd confirmed him pumping his fist. “As a crew, we had waited a very long time to get to that time in life, the place that is really taking place,” he recalled, “and I used to be very eager to emphasise, you recognize, let’s go get this executed!”

By the point the increase part was executed, 9 minutes into the flight, Gidzenko, Krikalev and Shepherd had attained an orbit of 144 x 113 miles (233 x 182 kilometers), inclined 51.6 levels to the equator. They deployed their craft’s communications and navigation antennas and electricity-generating photo voltaic arrays and opened the hatch between Soyuz TM-31’s cramped Descent Module and the marginally roomier Orbital Module.

The crew spent a typical two days in transit, earlier than Gidzenko oversaw a clean, automated docking on the aft longitudinal port of the station’s Zvezda module at 2:21 p.m. Baikonur time (4:21 a.m. EDT) on 2 November. On the time of Contact and Seize, Soyuz TM-31 and the ISS had been orbiting excessive above central Kazakhstan.

An hour later, at 3:23 p.m. Baikonur time (5:23 a.m. EDT), the hatch was opened into Zvezda’s major compartment. Gidzenko and Krikalev entered first, adopted by Shepherd, who needed to put together instruments to pattern the station’s ambiance and accumulate gasoline specimens.

“I believe Sergei was the primary man in,” Shepherd chuckled, “however then there was form of a really busy scramble to do the preliminary issues that we needed to do and, notably, to search out the TV hook-up and the TV cable in order that we may provide you with that downlink. We had been actually near the wire getting all that rigged and completely happy and we virtually missed it.”

The trio clasped fingers in unison, though Shepherd mirrored that they had been too busy to treat themselves as pioneers at the moment. “After the downlink was executed, we simply form of all sat again and mentioned, ‘Okay, we’ll name it a day’, as a result of it was very hectic.”

Requested about whether or not he thought of himself a pioneer, Krikalev’s considering mirrored that of Shepherd: their arrival was too busy, bringing the toddler station and its methods to life. “At that second, we had been considering of the current,” he mentioned, “though, subconsciously, we understood that was a sure threshold we had been speculated to cross.”

There might be no denying that it was a historic event. Though Soviet and Russian cosmonauts had occupied the Mir house station constantly from September 1989 by August 1999—greater than 3,600 days—it was anticipated that the ISS period would usher in an unbroken new age of human habitation of the heavens. “If all goes nicely on this and future missions,” NASA famous, “30 October 2000 would be the final day on which there have been no human beings in house.”

Twenty-three years on, these phrases proceed to ring true.