Blue-green Uranus could not appear like a lot by way of a telescope, however you may see its small disk at magnifications of 100x and extra. Even this close-up look from the Voyager 2 spacecraft fails to disclose a lot element. Credit score: NASA/JPL.

Uranus, the seventh planet from the Sun, orbits within the outer photo voltaic system, about two billion miles (3.2 billion kilometers) from Earth. It is a gigantic world – quadruple the diameter of Earth, with 15 instances the mass and 63 instances the quantity.

Unvisited by spacecraft for more than 35 years, Uranus inhabits one of many least explored areas of our solar system. Though scientists have realized some issues about it from telescopic observations and theoretical work since the Voyager 2 flyby in 1986, the planet stays an enigma.

It’s simple to divide the photo voltaic system into two giant teams: an inside zone with 4 rocky planets and an outer zone with 4 big planets. However nature is, as common, extra sophisticated. Uranus and Neptune, the eighth planet from the Sun, are vastly totally different from the others. Each are ice giants, composed largely of compounds reminiscent of water, ice, ammonia and methane; they’re locations the place the typical temperature is minus 320 to minus 350 levels Fahrenheit (minus 212 Celsius).

By way of recent discoveries of exoplanets – worlds outdoors our photo voltaic system which might be trillions of miles away – astronomers have realized that ice giants are widespread all through the galaxy. They problem our understanding of planetary formation and evolution. Uranus, comparatively near us, is our cornerstone for studying about them.

A brand new mission

Many within the area group – like me – are urging NASA to launch a robotic spacecraft to discover Uranus. Certainly, the 2023 decadal survey of planetary scientists ranked such a journey as the one highest precedence for a brand new NASA flagship mission.

This time, the spacecraft wouldn’t merely fly by Uranus on its method someplace else, as Voyager 2 did. As a substitute, the probe would spend years orbiting and finding out the planet, its 27 moons and its 13 rings.

It’s possible you’ll marvel, why ship a spacecraft to Uranus and never Neptune. It’s a matter of orbital structure. Due to the positions of each planets over the following twenty years, a spacecraft from Earth could have an easier trajectory to follow to succeed in Uranus than Neptune. Launched on the proper time, the orbiter would arrive at Uranus in about 12 years.

Listed here are only a few of the essential questions a Uranus orbiter would assist reply: What, precisely, is Uranus product of? Why is Uranus tilted on its side, with its poles pointed virtually immediately towards the Solar throughout summer season – which is totally different from all the opposite planets within the photo voltaic system? What’s producing Uranus’ strange magnetic field, formed in a different way than Earth’s and misaligned with the route the planet spins? How does atmospheric circulation work on an ice big? What do the solutions to all these questions inform us about how ice giants type?

However the progress scientists have made on these and different questions for the reason that Voyager 2 flyby, there’s no substitute for direct, close-up and repeated observations from an orbiting spacecraft.

The rings and people moons

The rings round Uranus, most likely product of soiled ice, are thinner and darker than these round Saturn. A Uranus orbiter would search for “ripples” in them, akin to waves on a lake. Discovering them would let scientists use the rings as a giant seismometer to assist us find out about the interior of Uranus, certainly one of its nice secrets and techniques.

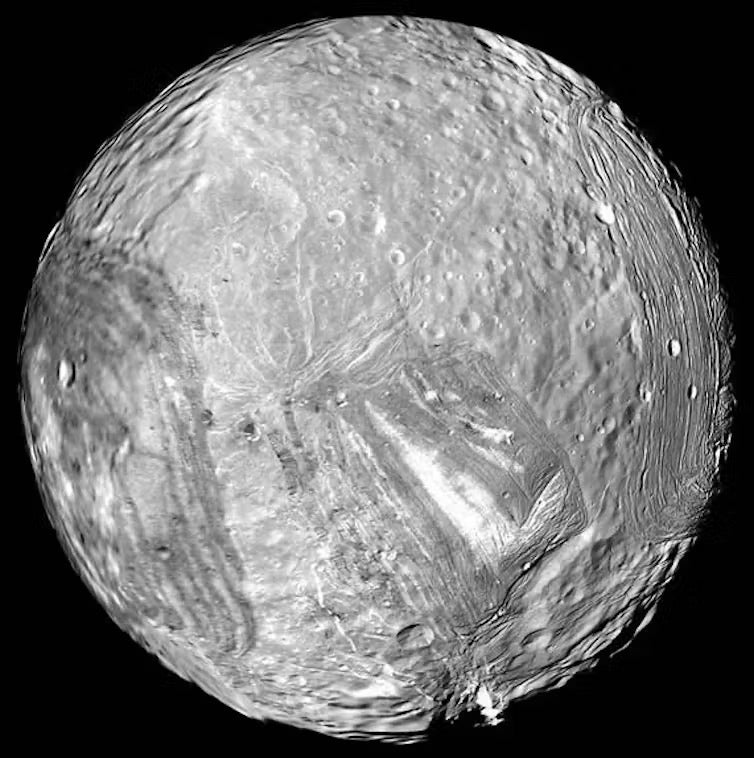

The moons, principally named after literary characters from the writings of Shakespeare and Pope, are primarily product of frozen mixes of ice and rock. 5 of the moons are significantly compelling. Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon are all large enough to be spherical and handled as miniature worlds in their very own proper.

Throughout its flyby, Voyager 2 took low-resolution images of the moons’ southern hemispheres. (Their northern hemispheres, nonetheless unseen, stay one of many main unexplored frontiers of our photo voltaic system.) These pictures embody pictures of ice volcanoes on Ariel – a tantalizing trace of previous geological and tectonic exercise and, presumably, subsurface water.

The potential of oceans and life

Which ends up in one of the thrilling components of the mission: Many planetary scientists theorize that Ariel, and maybe most or all the different 5 moons, could also be an ocean world harboring giant, underground our bodies of liquid water miles beneath the strong, icy floor. Discovering out whether or not any of the moons have oceans is without doubt one of the main objectives of the mission.

That is one purpose why an orbiter would most likely carry a magnetometer – to detect the electromagnetic interactions of an underground ocean as certainly one of its moons travels through Uranus’ magnetic field. Devices to measure the moons’ gravitational fields and cameras to review their floor geology would assist, too.

Liquid water is an important requirement for all times as we all know it. If oceans are detected, scientists will then wish to search for different substances for all times on the moons – such as energy, nutrients and organic matter.

Not a achieved deal

No launch date has been set for the mission, and there’s not but an official go-ahead from NASA on its funding. The fee would most likely be greater than a billion {dollars}.

One important issue to think about: The cosmos operates by itself timetable, and people spacecraft trajectories to Uranus will change over time because the planets transfer alongside their orbits. Ideally, NASA would launch a mission in 2031 or 2032 to maximise trajectory comfort and reduce journey time. That point span is lower than it might appear; it takes years of planning – and years extra of setting up the spacecraft – to be prepared for launch. That’s why the time is now to start out the method and fund a mission to this fascinating world.

Mike Sori is an assistant professor of planetary science at Purdue College.

This text first appeared on The Conversation. You may learn the original here.