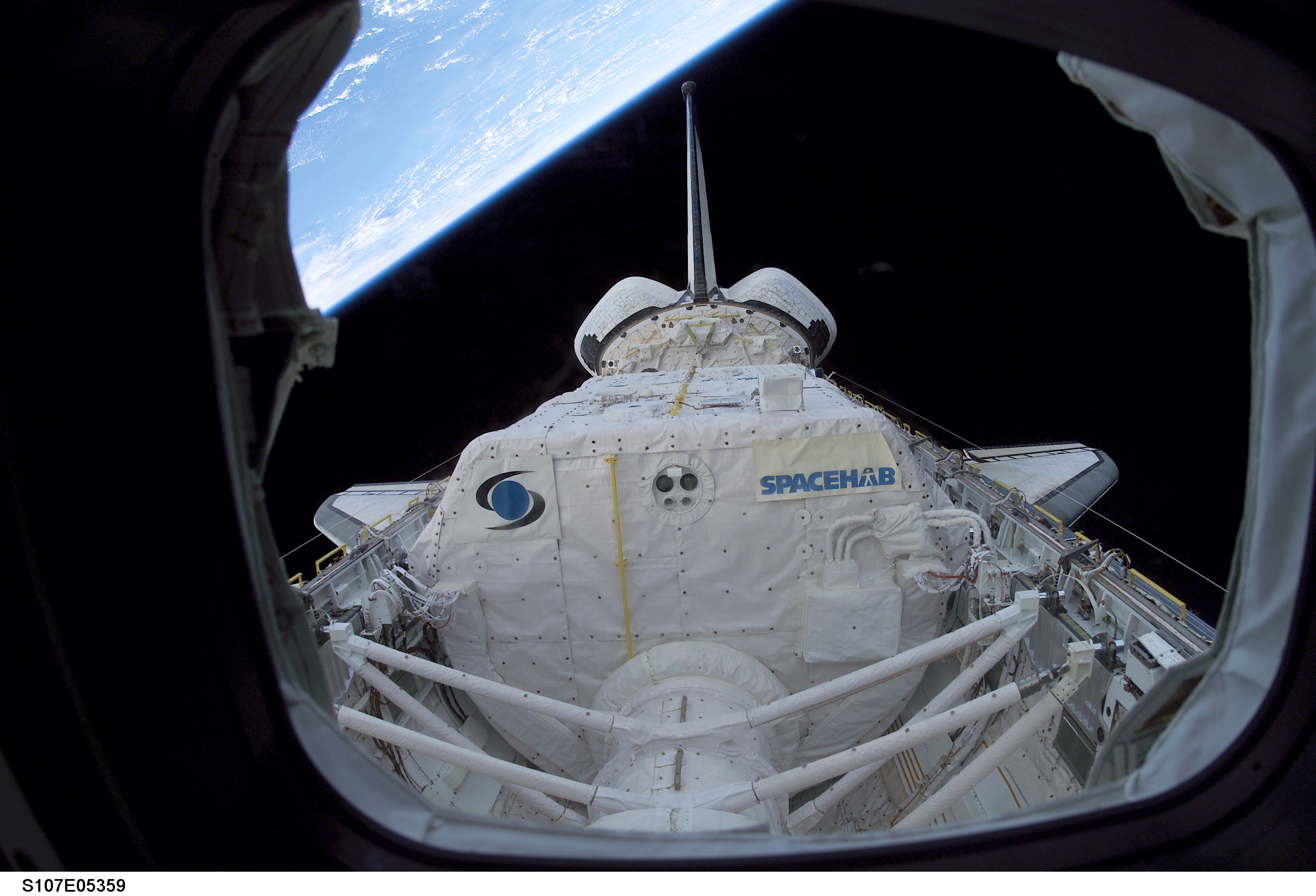

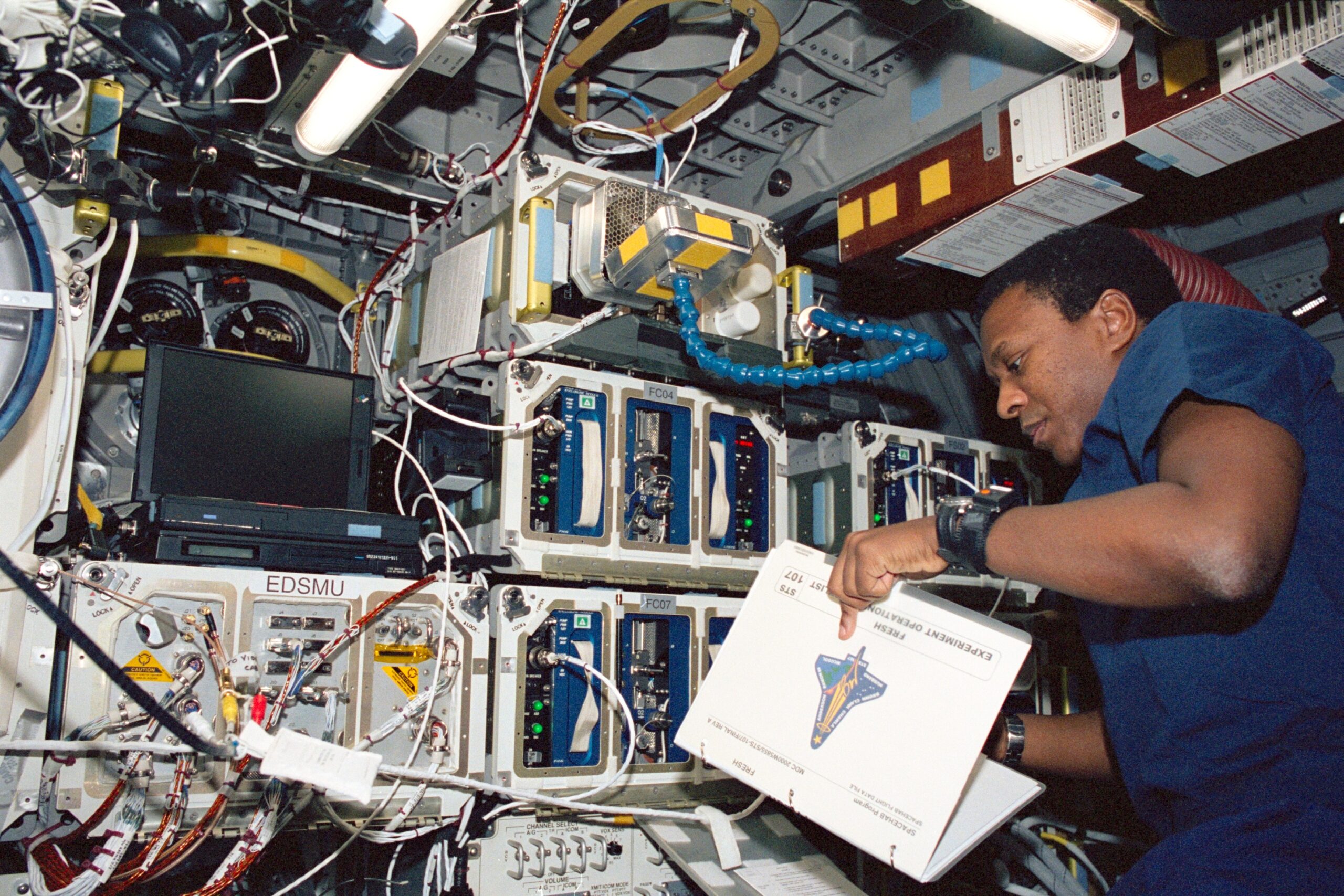

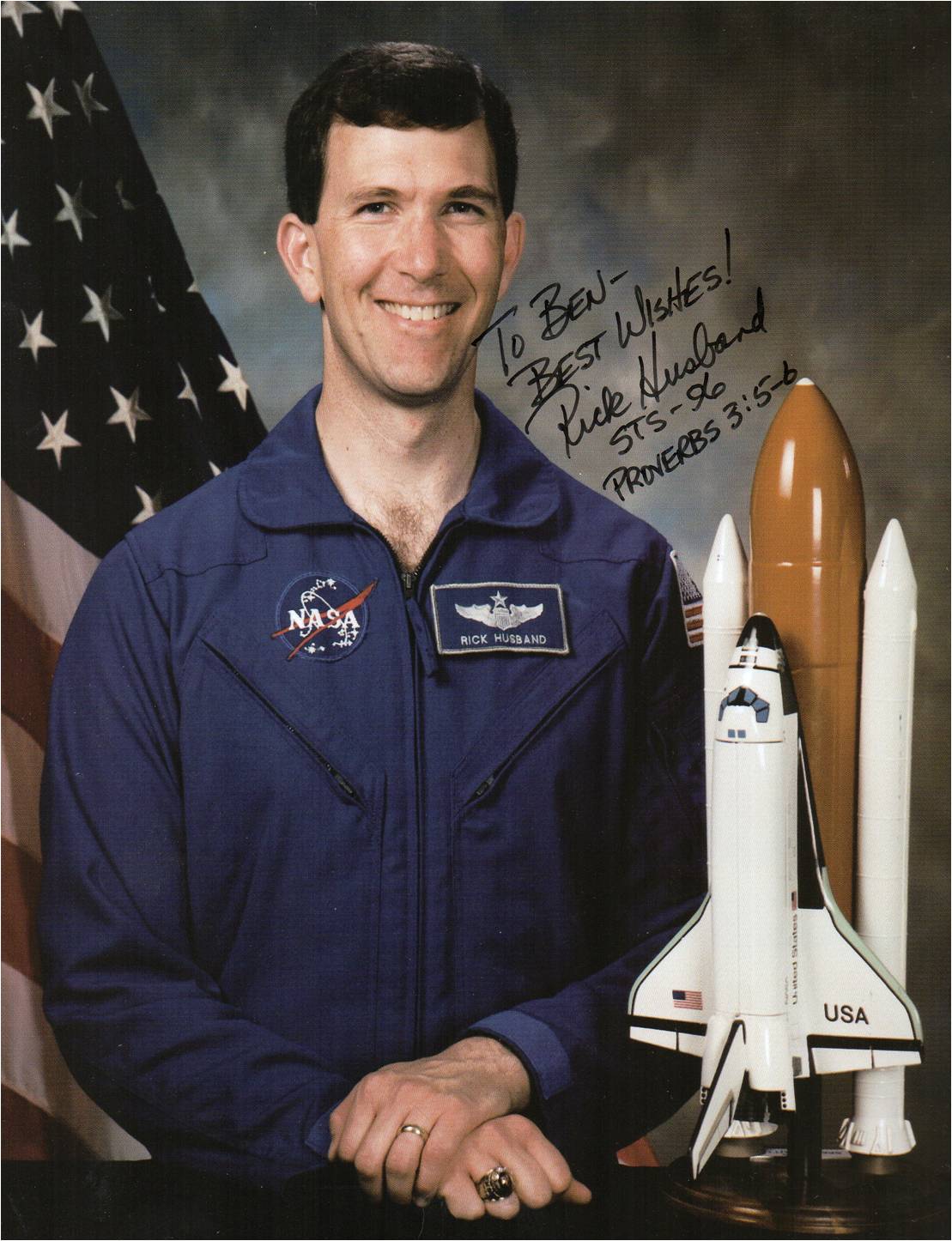

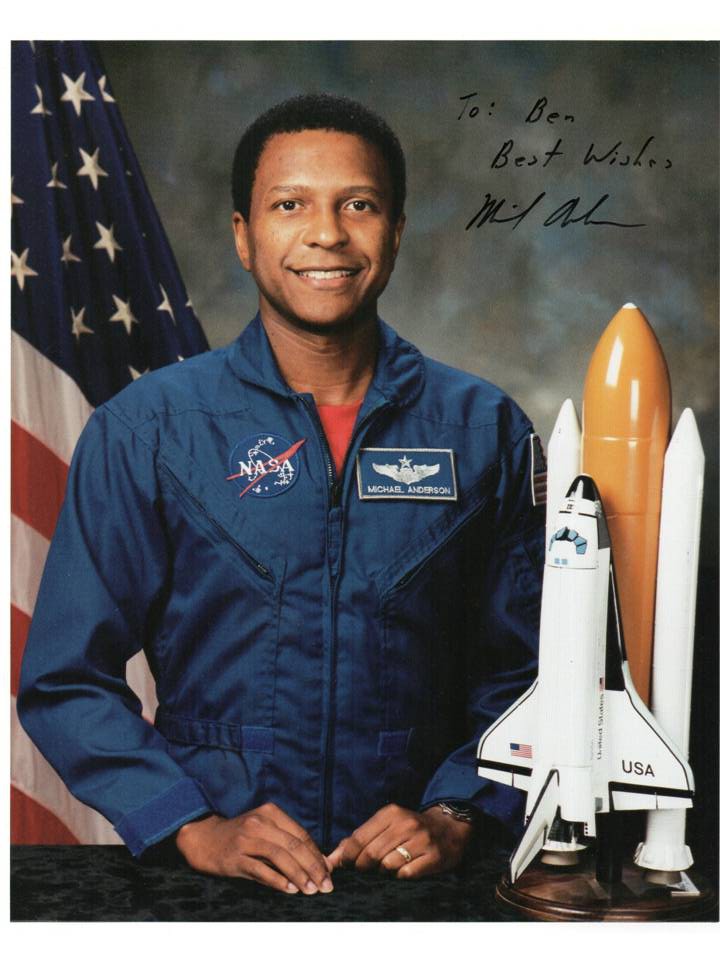

For the second half of January in 2003, the seven women and men of shuttle Columbia’s STS-107 crew—Commander Rick Husband, Pilot Willie McCool, Mission Specialists Laurel Clark, Dave Brown, Mike Anderson and Kalpana “Okay.C.” Chawla and Payload Specialist Ilan Ramon of Israel—labored around-the-clock on 80 scientific experiments spanning a wide range of disciplines from life sciences to fluid physics and supplies processing to Earth observations. Eighty-seven missions after the calamitous lack of Challenger, shuttles had serviced the Hubble House Telescope (HST), docked 9 occasions with Russia’s Mir orbital complicated and begun constructing the Worldwide House Station (ISS).

The shuttle, in fact, remained an inherently hazardous machine. However the robustness of the 4 surviving orbiters—Discovery, Endeavour, Columbia and Atlantis—had been amply demonstrated, again and again, and their shortfalls had been effectively understood. Or so it appeared. For these shortfalls got here residence to roost with horrifying suddenness 21 years in the past, on the morning of Saturday, 1 February 2003.

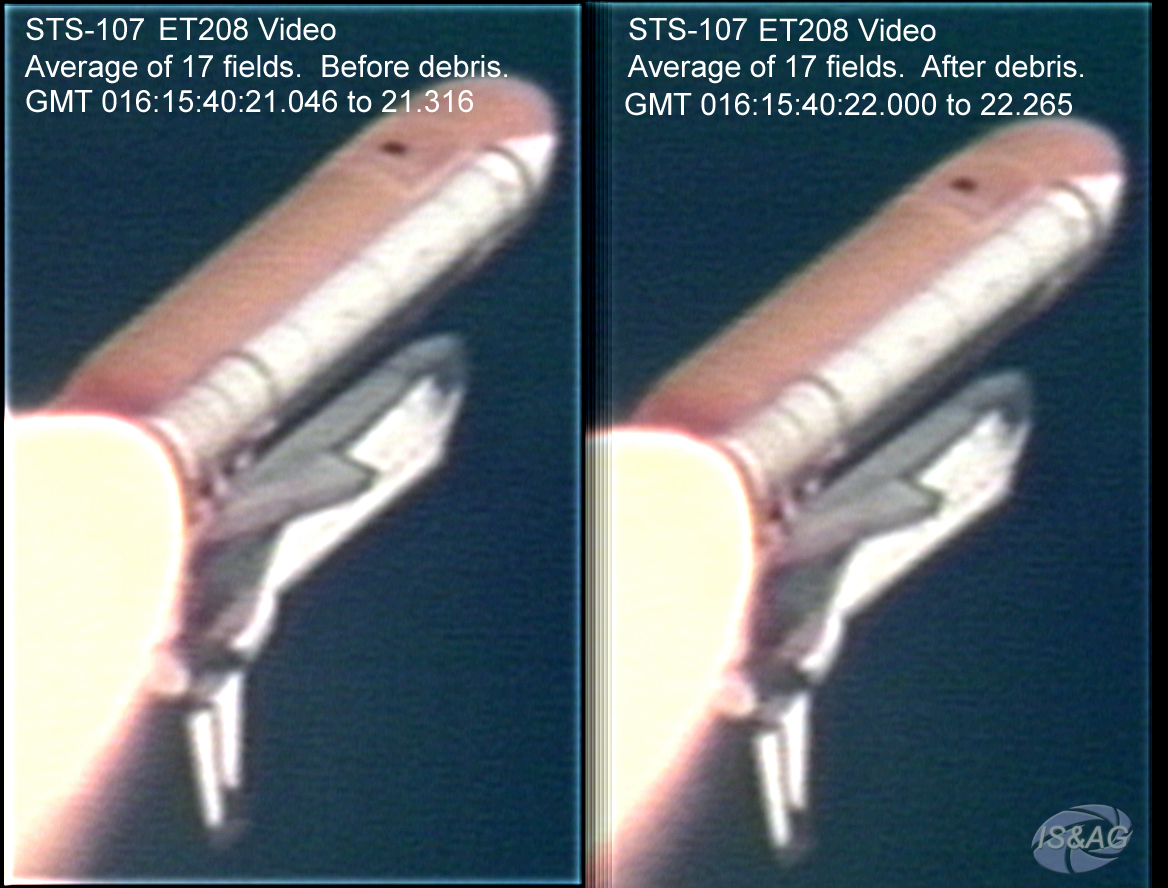

Throughout greater than twenty years of operational service, the shuttle fleet weathered last-second shutdowns on the launch pad, fundamental engine issues throughout liftoff and later within the ascent regime, in addition to extreme Thermal Safety System (TPS) harm throughout the excessive dynamism of atmospheric re-entry. And when a briefcase-sized chunk of insulating foam was noticed on the STS-107 launch video falling from the Exterior Tank (ET) at T+82 seconds and hitting Columbia’s left wing—at exactly the spot the place Bolstered Carbon Carbon (RCC) would later guard the ship in opposition to probably the most extreme re-entry temperatures—concern was elevated, however in the end dismissed.

It was a dismissal as ill-judged as declaring the Titanic to be unsinkable.

The video footage from STS-107’s launch on 16 January provided little indication of what, if any, harm the froth strike had brought about, save for an enormous bathe of particles. It was unclear if these particles originated from the impression of the froth itself or from shattered items of the RCC panels. If the latter, it didn’t bode effectively for Columbia’s re-entry, for the panels guarded the car in opposition to the brunt of three,000-degree-Celsius (5,400-degree-Fahrenheit) extremes throughout the hypersonic return to Earth.

Senior managers doubted {that a} foam strike—an occasion which had occurred on earlier missions—may conceivably be a “security of flight” concern. This didn’t, nonetheless, stop an evaluation of a potential state of affairs wherein the RCC had been breached.

On 31 January, engineer Kevin McCluney provided a hypothetical description to his colleagues on the Johnson House Middle’s (JSC) flight management crew of the form of knowledge “signature” they may count on to obtain if the worst ought to occur.

Allow us to suppose, stated McCluney—outlined by Michael Cabbage and William Harwood of their harrowing account of the tragedy, Comm Test—that a big gap had been punched by way of one of many shuttle’s RCC panels, enabling super-heated plasma to enter the airframe.

“Let’s surmise,” he informed them, “what kind of signature we’d see if a restricted stream of plasma did get into the wheel effectively [of Columbia’s main landing gear], roughly from entry interface till about 200,000 toes (60 kilometers); in different phrases, a 10-15-minute window.” Little may McCluney probably have guessed that his “signature” would virtually precisely mirror the occasions which befell Columbia on Saturday, 1 February 2003.

“First could be a temperature rise for the tires, brakes, strut actuator and the uplock actuator return…”

At 8:52:17 a.m. EST, 9 minutes after entry interface—the purpose at which the shuttle started to come across the tenuous higher traces of the “wise” environment—Entry Flight Director LeRoy Cain and his crew noticed the primary uncommon knowledge on their screens. Cain had begun his shift on console earlier that morning, with an up-tempo “Let’s go get ’em, guys,” earlier than giving Husband the go-ahead to carry out the irreversible de-orbit burn to drop Columbia out of orbit and onto an hour-long path to land on the Kennedy House Middle’s (KSC) Shuttle Touchdown Facility (SLF) at 9:16 a.m. EST.

A lot of the entry profile was managed by the shuttle’s Basic Function Computer systems (GPCs), however with 23 minutes remaining earlier than landing, Upkeep, Mechanical Arm and Crew Programs (MMACS) Officer Jeff Kling noticed one thing peculiar in his knowledge. It was what flight controllers termed an “off-nominal occasion”.

As later described by Cabbage and Harwood, Kling seen two downward-pointing arrows seem subsequent to readings from a pair of sensors deep inside Columbia’s left wing. They had been designed to measure hydraulic fluid temperatures in traces resulting in the elevons.

A number of seconds later, two extra sensors failed. The eye of Kling was captivated; it appeared for all of the world that the wiring to all 4 sensors had been minimize.

Kling and his crew tried to fathom a standard “thread” to elucidate the fault. However none was forthcoming.

Kling spoke on to Cain. “FYI, I’ve simply misplaced 4 separate temperature transducers on the left facet of the car,” he started, cautiously. “Hydraulic return temperatures. Two of them on System One and one in every of Programs Two and Three.”

“4 hyd return temps?” queried Cain.

“To the left outboard and left inboard elevon.”

Cain’s ideas mirrored these of Kling: was there a standard root trigger for all 4 sensors to have failed in such shut bodily and temporal proximity to 1 one other? When Kling asserted that there was “no commonality” between the failures, Cain was perplexed, however immediately thought again to the froth strike. In subsequent interviews, he would admit that his rapid worry was that sizzling gasoline had labored its method by way of a breach in Columbia’s left wing and was one way or the other affecting the inside techniques.

Nonetheless, Steering, Navigation and Management Officer (GNC) Mike Sarafin assured him that total car efficiency because it crossed the California-Nevada state line at 22.5 occasions the velocity of sound remained nominal. Was Kling proud of all different hydraulic techniques? Kling replied that, sure, every little thing else was functioning usually.

“Tire pressures would rise, given sufficient time, and assuming the tires don’t get holed,” continued Kevin McCluney’s chilling prediction, “the information would begin dropping out as {the electrical} wiring is severed.”

All of the sudden, at 8:58 a.m. EST, Husband made his first radio transmission since entry interface a quarter-hour earlier. He began to name Mission Management, however his phrases had been abruptly minimize off. A number of seconds later got here a lack of temperature and stress knowledge from each the inboard and outboard tires of Columbia’s touchdown gear within the left effectively.

If the tires had been holed or dropping stress, it was very unhealthy information, for STS-107 was a “heavyweight” mission with the totally loaded Spacehab science module and experiment pallet. A “wheels-up” stomach touchdown was doubtless not survivable. The astronauts would wish to carry out a never-before-tried bailout, using an escape pole system carried out after Challenger, however this might not be tried till Columbia was at a lot decrease altitude and at a lot decrease relative airspeed.

“Knowledge loss would come with that for tire pressures and temperatures, brake pressures and temperatures,” concluded McCluney.

After listening to Kling’s report, astronaut Charlie Hobaugh—the lead Capcom on responsibility that morning—referred to as Husband to tell him of the anomalous tire stress messages. Hobaugh additionally requested Husband to repeat his final remark.

However there was no reply from Columbia. By now, Cain was urgent Kling for solutions on whether or not the messages had been because of defective instrumentation however was suggested that each one related sensors had been studying “off-scale-low”—they’d merely stopped working.

Seconds later, at 8:59:32 a.m., Husband tried once more to contact Mission Management. These had been to be the final phrases ever obtained from Columbia.

“Roger,” he stated, presumably acknowledging Hobaugh’s earlier stress name, “uh, buh…” At that time, abruptly, his phrases had been minimize off in mid-sentence, along with the stream of information from the orbiter.

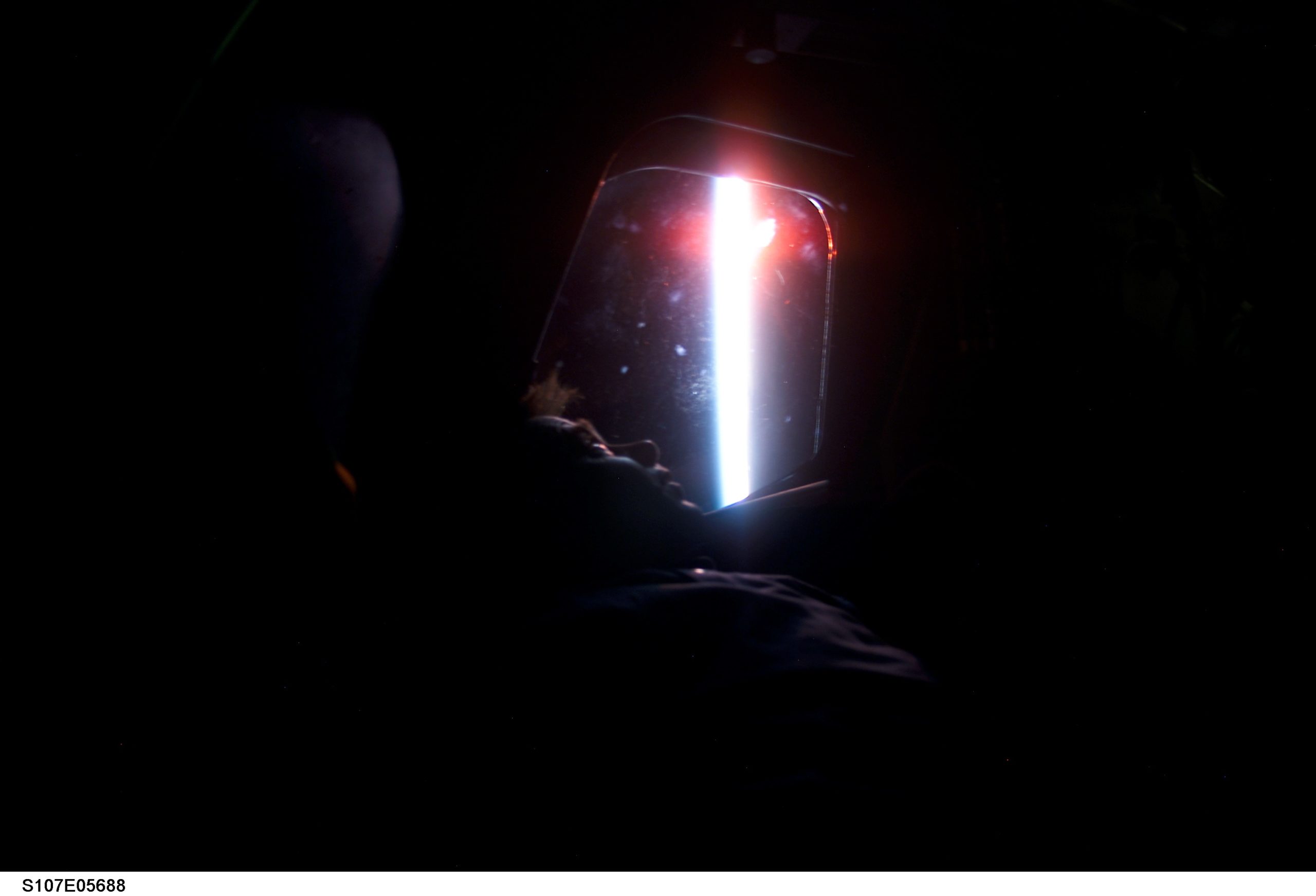

Communications had been by no means restored. Thirty-two seconds later, a ground-based observer with a camcorder shot video footage of a number of particles contrails streaking like tears throughout the Texas sky.

With the telemetry damaged, the environment in Mission Management was changing into more and more uncomfortable. Kling informed Cain there was no frequent thread between the tire stress messages and the hydraulic sensor failures; furthermore, different instrumentation for monitoring the positions of the orbiter’s nostril and fundamental touchdown gear had additionally been misplaced.

Because the seconds of radio silence stretched longer, Cain requested Instrumentation and Communications Officer (INCO) Laura Hoppe how lengthy she anticipated the intermittent “comm” to final. She admitted that she anticipated some ratty comm however was stunned and puzzled by how protracted and “stable” it was.

“Columbia, Houston, comm examine,” radioed Hobaugh at 9:03 a.m. His phrases had been greeted solely by static and by the echo of his personal voice within the deathly-silent Mission Management. A minute later, he repeated the decision. Once more, there was no reply.

Half a continent away, at KSC, astronauts Jerry Ross and Bob Cabana had been chatting outdoors the convoy commander’s van on the SLF, once they heard that communications with Columbia had been misplaced. At first, they had been unconcerned—that’s, till they had been knowledgeable that highly effective long-range radars on the Cape, meant to lock onto the incoming orbiter at 9:04 a.m. and monitor its last strategy, noticed nothing coming over the horizon.

In Cain’s phrases, that provided the ultimate punch-in-the-stomach affirmation that each one hope was misplaced. “That was absolutely the black-and-white finish,” he stated later. “If the radar is trying and there’s nothing coming over the horizon, the car just isn’t there.”

In contrast to an plane, which may modify its flight profile to make secondary approaches, the shuttle had just one shot to make a pinpoint touchdown. Its trajectory by way of the environment could possibly be timed to the second and landing was anticipated at 9:16 a.m. Climate knowledge additionally made it potential to foretell how far down the runway—about 1,500 toes (460 meters)—the shuttle would land.

On the Cape, the assembled crowds noticed the countdown clock tick to zero…after which start ticking upwards once more as 9:16 got here and went. No trademark sonic booms had been heard. No signal of the tiny black-and-white dot of the orbiter had been seen. Veteran shuttle commander Steve Lindsey—later to change into Chief of the Astronaut Workplace—was one of many escorts for the STS-107 households and his blood ran chilly. One thing was terribly fallacious.

Standing subsequent to NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe that morning was former astronaut Invoice Readdy, now serving because the company’s Affiliate Administrator for House Flight. O’Keefe would describe the previous fighter pilot and veteran shuttle commander as ashen-faced and visibly trembling. Jerry Ross was a couple of months into his new job as head of the Cape’s Car Integration Check Group (VITT) and his first act was to say a short prayer.

In Texas, police had been being inundated with 911 calls, reporting unusual lights within the sky, loud explosions, and situations of falling particles. CNN shortly picked up on the tales and commenced reporting them. In Mission Management, nonetheless, televisions weren’t tuned to outdoors broadcasts. It was an off-duty NASA engineer, Michael Garske, who watched the shuttle cross overhead from the roadside, south of Houston, and referred to as colleague Don McCormack in Mission Management with the information.

“Don, Don, I noticed it,” Garske cried, paraphrased by Cabbage and Harwood. “It broke up!”

“Decelerate,” McCormack replied. “What are you telling me?”

“I noticed the orbiter. It broke up!”

Sitting behind LeRoy Cain on the similar time, veteran flight director Phil Engelauf obtained a name from off-duty flight director Bryan Austin, who offered first-hand testimony. By this time, though nobody in Mission Management had bodily seen the proof of the catastrophe, they’d resigned themselves to it.

At 9:05 a.m., Cain requested Flight Dynamics Officer (FDO) Richard Jones when he may count on monitoring from the long-range radars in Florida. One minute in the past, got here the reply.

Now, as Engelauf relayed Austin’s emotional report back to Cain, the flight director slowly shook his head, composed himself and turned to the silent management room to declare an emergency. At 9:12 a.m., he instructed Floor Management (GC) Officer Invoice Foster to “lock the doorways”—a de facto admission that each one hope was gone—and ordered flight controllers to not go away the constructing, however to start preserving their knowledge and writing up their logbook notes to be used within the subsequent investigation.

“OK,” Cain started, “all flight controllers on the Flight loop, we have to kick off the FCOH [Flight Control Operations Handbook] contingency plan process, FCOH guidelines, web page 2.8-5.” He then proceeded to speak them by way of the required actions: preserving logbook entries and show printouts, speaking solely on the Flight loop and limiting outdoors phone calls and transmissions. “No telephone calls, no knowledge, in or out,” he informed them.

9 hundred miles (1,500 kilometers) to the east, in Florida, the STS-107 households had been shepherded from the touchdown web site to the crew quarters by 9:30 a.m. It was left to Bob Cabana to interrupt the horrible information—considered one of his worst jobs in his astronaut profession.

Mission Management, he defined, had not picked up any radio beacon alerts which might have been activated if the crew had managed to bail out of Columbia. Regardless, the orbiter was at an altitude of round 40 miles (64 kilometers) and touring at practically 15,000 miles per hour (24,000 kilometers per hour) when it disintegrated. That alone provided not even the faintest hope of being survivable.

Later that morning, close to Hemphill, Texas, Roger Coday discovered some human stays. He stated a short prayer and constructed a tiny picket cross by the roadside.