Mariner 10, launched in 1973, was the primary single mission to discover two planets. Credit score: NASA.

To the traditional Romans, Mercury was the messenger of the gods, his winged sandals adroitly whisking the maestro of luck and trickery to do his divine masters’ bidding. Small marvel that the closest planet to the Solar was named in his honor: Crater-pocked Mercury whips round our dad or mum star in 88 days at a imply distance of 36 million miles (58 million kilometers), two-thirds nearer than Earth.

Brutalized by aeons of remorseless meteoroid bombardment, Mercury is a barren, broiling world of extremes. In its coal-dark sky, the Solar seems 11 instances brighter, thrice greater, and plenty of instances hotter than right here on Earth. Its 3:2 spin-orbit resonance and orbital eccentricity produced a Moon-like floor of mountains and plains, scarps and valleys, frozen to minus 170 levels Celsius (minus 270 levels Fahrenheit) at night time then baked as excessive as 420 levels Celsius (790 levels Fahrenheit) within the mercurian daytime.

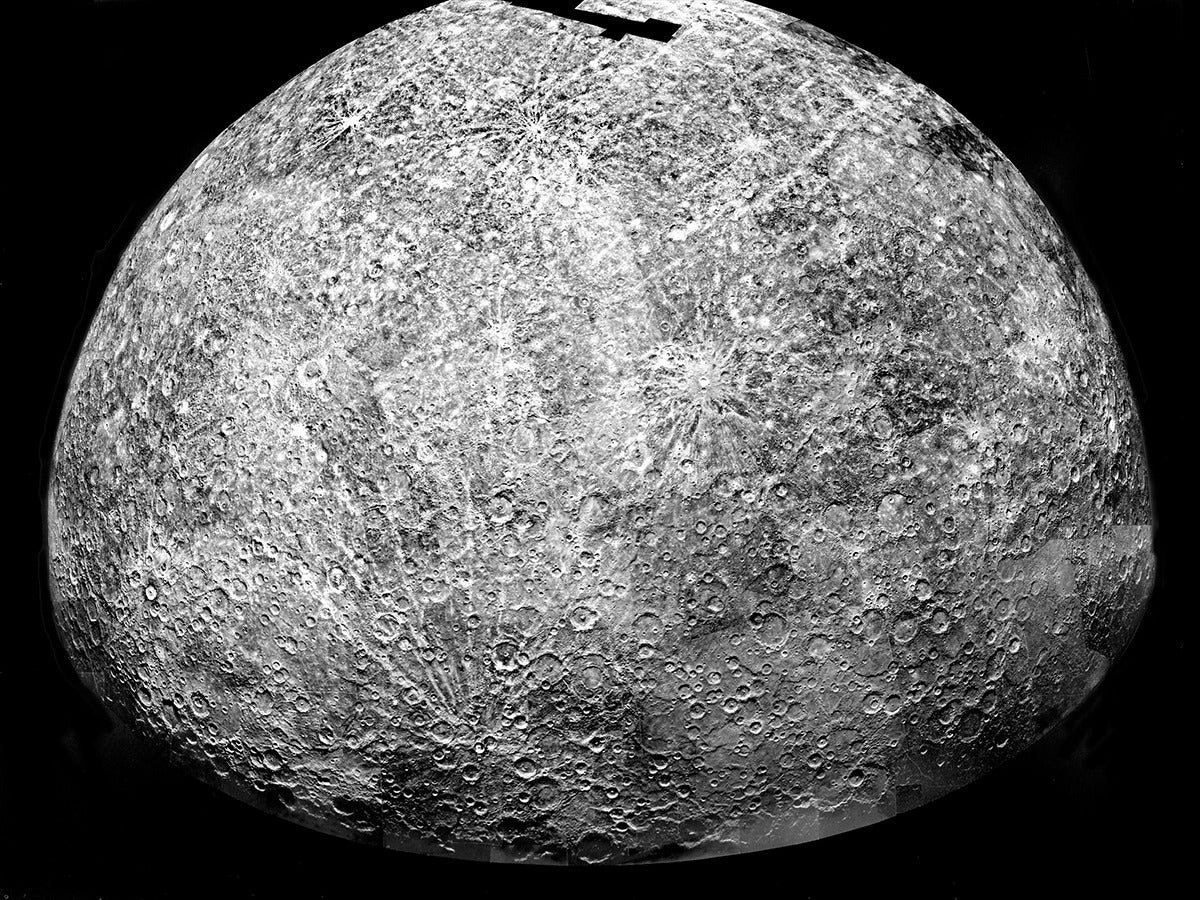

Fifty years in the past, humanity gained its first up-close glimpse of this battered world when NASA’s Mariner 10 spacecraft made the primary of three Mercury encounters. Its seven science devices revealed closely cratered highlands and rolling lowlands, the Caloris influence basin, and surprisingly (in view of Mercury’s geological deadness), an intrinsic magnetic subject and hints of an iron-rich core.

But when Mariner 10’s mission was historic, so was the Boeing-built spacecraft itself, which for the primary time used the gravity of 1 world (Venus) to achieve one other (Mercury) and in doing so visited two planets for the primary time. It used extant {hardware} and expertise to maintain prices down, however engineers acknowledged that voyaging inside 0.4 astronomical models (AU; 1 astronomical unit is the same as the typical Earth-Solar distance of 93 million miles or 150 million km) of the Solar would impose 4.5 instances higher photo voltaic radiation at Mercury than at Earth.

Get on the Mariner 10 bus

As such, Mariner 10’s octagonal spacecraft “bus” was guarded with thermal blankets of beta material (a mix of aluminized Kapton and glass-fiber sheets handled with Teflon) plus a sunshade and specialised louvers to control inside temperatures. Its two photo voltaic arrays, with a wingspan of 26 toes (7.6 meters), had been rotatable via their lengthy axes to reduce photo voltaic heating and preserve them under 115 C (239 F).

Mariner 10 bristled with cameras, an infrared radiometer to evaluate the thermal properties of Mercury’s floor, an ultraviolet spectrometer to smell out a putative ambiance, sensors to research interactions between the photo voltaic wind and cosmic radiation, two magnetometers on a 19-foot-long (5.8 m) hinged growth to hunt proof of an intrinsic magnetic subject and a radio science toolkit to take mass and gravitational measurements. A 4.6-foot (1.4 m) high-gain antenna transmitted information at charges of 117.6 kilobits per second.

Earlier Mariners flew in pairs to hedge in opposition to failure, however funds constraints had cost-capped Mariner 10 at $98 million. That allowed a spare spacecraft to be in-built case of failure, however NASA decreed it may solely fly if the deadly flaw was recognized and resolved inside two weeks. With Mariner 10 set to fly on Nov. 3, 1973, within the occasion of catastrophe the spare needed to be able to go no later than Nov. 21.

In the meantime, Italian physicist Giuseppe Colombo recommended that Mariner 10’s trajectory following its March 1974 encounter of Mercury would allow a second flyby of the planet six months later. That layered higher complexity onto an already complicated mission however carried the potential to tremendously develop the scientific yield from an unknown world.

Mariner 10 launches in 1973

Mariner 10 launched atop an Atlas-Centaur rocket from Cape Canaveral’s Pad 36B at 12:45 a.m. EST on Nov. 3, 1973. Roaring aloft underneath 430,000 kilos (195,000 kilograms) of thrust, the Atlas booster shut down as deliberate 4 minutes into the flight, leaving the Centaur higher stage to carry out two burns to firstly insert Mariner 10 into an Earth-parking orbit, then increase it into deep area.

It was a dangerous maneuver. By no means earlier than had two upper-stage burns been finished on a U.S. planetary mission; an engine fault may spell the tip for Mariner 10. Aside from a drifting gyro, the Centaur carried out admirably, pushing the 1,100-pound (500 kg) spacecraft out of Earth’s gravitational clutches and into interplanetary area at 25,458 mph (40,969 km/h). Forward in 94 days lay its first planetary goal: Venus.

However the cruise proved removed from untroubled. Hours after launch, a canopy didn’t open on an electrostatic analyzer, nixing its use in an electron spectrometer experiment. Mariner 10’s star tracker repeatedly misplaced its lock on Canopus, locking its gaze as an alternative onto stray flecks of paint. A number of laptop resets and high-gain antenna glitches turned a low-level headache for NASA engineers right into a full-blown, three-month migraine.

Worse, short-circuiting heaters on the spacecraft’s cameras didn’t activate, threatening everlasting harm from the chilly of deep area. Happily, the cameras’ regular mode of operation stored them heat sufficient to hover above essential temperature limits; they had been left switched on throughout the cruise to Venus. Then, in an surprising piece of excellent fortune, in January 1974 the warmers began working once more.

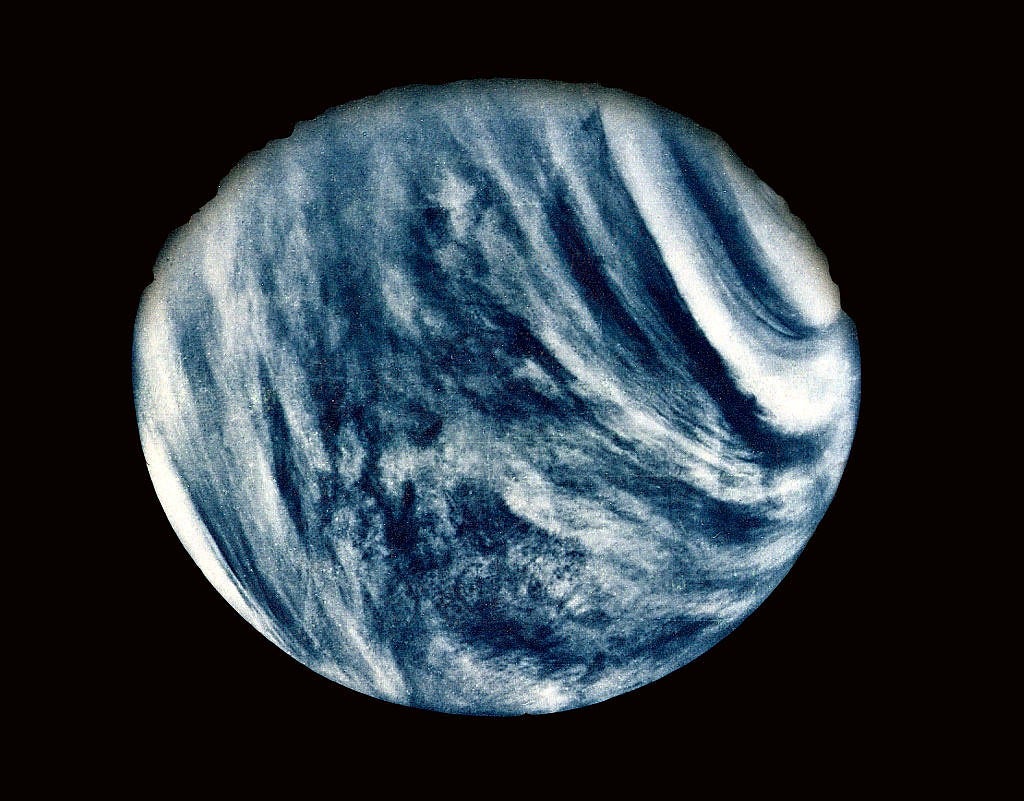

On Feb. 5, Mariner 10 swept 3,584 miles (5,768 km) over Venus’ cloud-cloaked façade, buying 4,165 images and gathering information on atmospheric constructions and near-surface temperatures. Close to-ultraviolet measurements had been taken of high-altitude, cirruslike chevron clouds.

However it proved a whistlestop tour. Venus’ gravity shaved the spacecraft’s velocity from 82,785 mph (133,230 km/h) to 72,215 mph (116,220 km/h), bending its flight path and reshaping its elliptical photo voltaic orbit to intersect Mercury. Seven weeks after passing Venus, and 146 days since departing Earth, the tiny planet emerged from the gloom.

Mariner 10 started photographing Mercury a number of days earlier than closest strategy, at first intermittently, then taking pictures a body each 42 seconds by March 28. Subsequent day, the spacecraft hurtled inside 437 miles (703 km) of a world recognized for hundreds of years as little greater than a faint blob in telescope eyepieces, nearly misplaced within the Solar’s glare. Heading outbound, it continued shuttering pictures till April 3.

Two thousand photos streamed to expectant scientists again residence. The Mercury I information uncovered a worldwide magnetic subject two orders of magnitude feebler than Earth’s personal, arguably Mariner 10’s most surprising discover. And an enormous influence basin crept teasingly into view, its yawning maw spanning over 830 miles (1,340 km), wider than Texas. Ringed by mile-high mountains, its location on the planet’s broiling, Solar-facing hemisphere earned it the apt moniker of Caloris Basin – Latin for “scorching.”

Looping again across the Solar, Mariner 10 returned for its second go to, Mercury II, over the planet’s southern hemisphere on Sept. 21. Though the flyby distance of 29,870 miles (48,070 km) was wider, the viewing geometries had been higher. Extra information was additionally harvested from the spacecraft by way of enhancements to NASA’s Deep Area Community (DSN), together with the microwave antennas in Goldstone, California.

Six months later, on March 16, 1975, Mariner 10 encountered the planet a 3rd time for Mercury III, passing over the north polar area at 203 miles (327 km), its closest but. A failed tape recorder and restrictions in data-reception charges meant solely the central quarter of 300 high-resolution images was obtained, however Mariner 10 managed to the picture floor options as small as 328 toes (100 m) throughout.

A lot of this exceptional prolonged mission was solely attainable due to engineers tripling the quantity of hydrazine propellant for course correction maneuvers and further nitrogen gasoline for its thrusters. However after Mercury III, gasoline was low and the tip was nigh. After touring for 506 days and overlaying a billion miles (1.6 billion km), Mariner 10’s transmitter was shut down on March 24, 1975, and the mission concluded.

It had been a exceptional triumph, though the geometry of Mercury’s orbit throughout all three encounters meant the identical facet of the planet was sunlit every time, enabling Mariner 10 to map barely 40 to 45 % of the floor. However, the spacecraft’s 2,800 images revealed rugged highlands and clean lowlands. Chains and clusters of craters embayed the highlands, and Mariner 10 information pointed to the existence of a tenuous exosphere of hydrogen and helium atoms captured from the photo voltaic wind, plus a bulk density in step with a large core, wealthy in iron and nickel.

Floor observations and NASA’s Messenger spacecraft have since mapped the planet in its entirety, hinting at water-ice in completely shadowed polar craters. Europe’s BepiColombo mission will attain Mercury in December 2025 for its personal prolonged orbital survey. And Mariner 10, which first make clear this odd little world, now drifts silently in heliocentric area, unseen and untracked since contact went lifeless a half-century in the past.