Round noon on June 13 final yr, my colleagues and I had been scanning the skies once we thought we had found a wierd and thrilling new object in house. Utilizing an enormous radio telescope, we noticed a blindingly quick flash of radio waves that seemed to be coming from someplace inside our galaxy.

After a yr of analysis and evaluation, we’ve finally pinned down the supply of the sign — and it was even nearer to residence than we had ever anticipated.

A shock within the desert

Our instrument was situated at Inyarrimanha Ilgari Bundara, the CSIRO Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory in distant Western Australia, the place the sky above the pink desert plains is huge and stylish.

We had been utilizing a brand new detector on the radio telescope referred to as the Australian Sq. Kilometre Array Pathfinder — or ASKAP — to seek for uncommon flickering alerts from distant galaxies known as fast radio bursts.

We detected a burst. Surprisingly, it confirmed no proof of a time delay between excessive and low frequencies — a phenomenon referred to as “dispersion”.

This meant it should have originated inside a number of hundred mild years of Earth. In different phrases, it should have come from inside our galaxy — not like different quick radio bursts which have come from billions of light years away.

An issue emerges

Quick radio bursts are the brightest radio flashes within the Universe, emitting 30 years’ value of the Solar’s vitality in lower than a millisecond — and we solely have hints of how they’re produced.

Some theories recommend they’re produced by “magnetars” — the extremely magnetised cores of huge, useless stars — or arise from cosmic collisions between these useless stellar remnants. No matter how they happen, quick radio bursts are additionally a exact instrument for mapping out the so-called “missing matter” in our Universe.

Once we went again over our recordings to take a more in-depth a take a look at the radio burst, we had a shock: the sign appeared to have disappeared. Two months of trial and error glided by, till the issue was discovered.

ASKAP consists of 36 antennas, which will be mixed to behave like one gigantic zoom lens six kilometres throughout. Identical to a zoom lens on a digital camera, for those who attempt to take an image of one thing too shut, it comes out blurry. Solely by eradicating a number of the antennas from the evaluation — artificially lowering the scale of our “lens” — did we lastly make a picture of the burst.

We weren’t excited by this — the truth is, we had been disillusioned. No astronomical sign could possibly be shut sufficient to trigger this blurring.

This meant it was in all probability simply radio-frequency “interference” — an astronomer’s time period for human-made alerts that corrupt our information.

It’s the type of junk information we’d usually throw away.

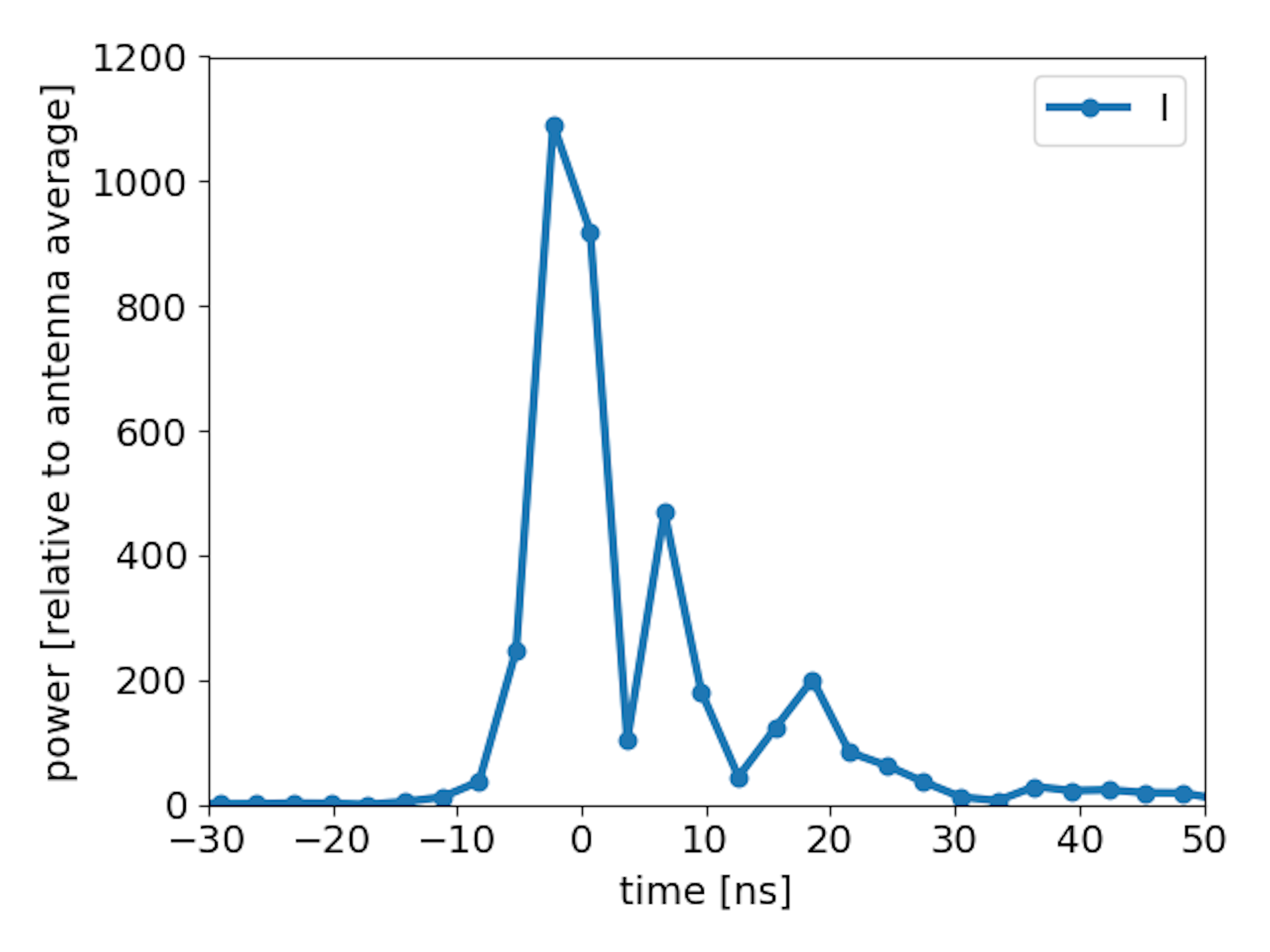

But the burst had us intrigued. For one factor, this burst was quick. The quickest recognized quick radio burst lasted about 10 millionths of a second. This burst consisted of an especially vibrant pulse lasting a number of billionths of a second, and two dimmer after-pulses, for a complete period of 30 nanoseconds.

So the place did this amazingly quick, vibrant burst come from?

A zombie in house?

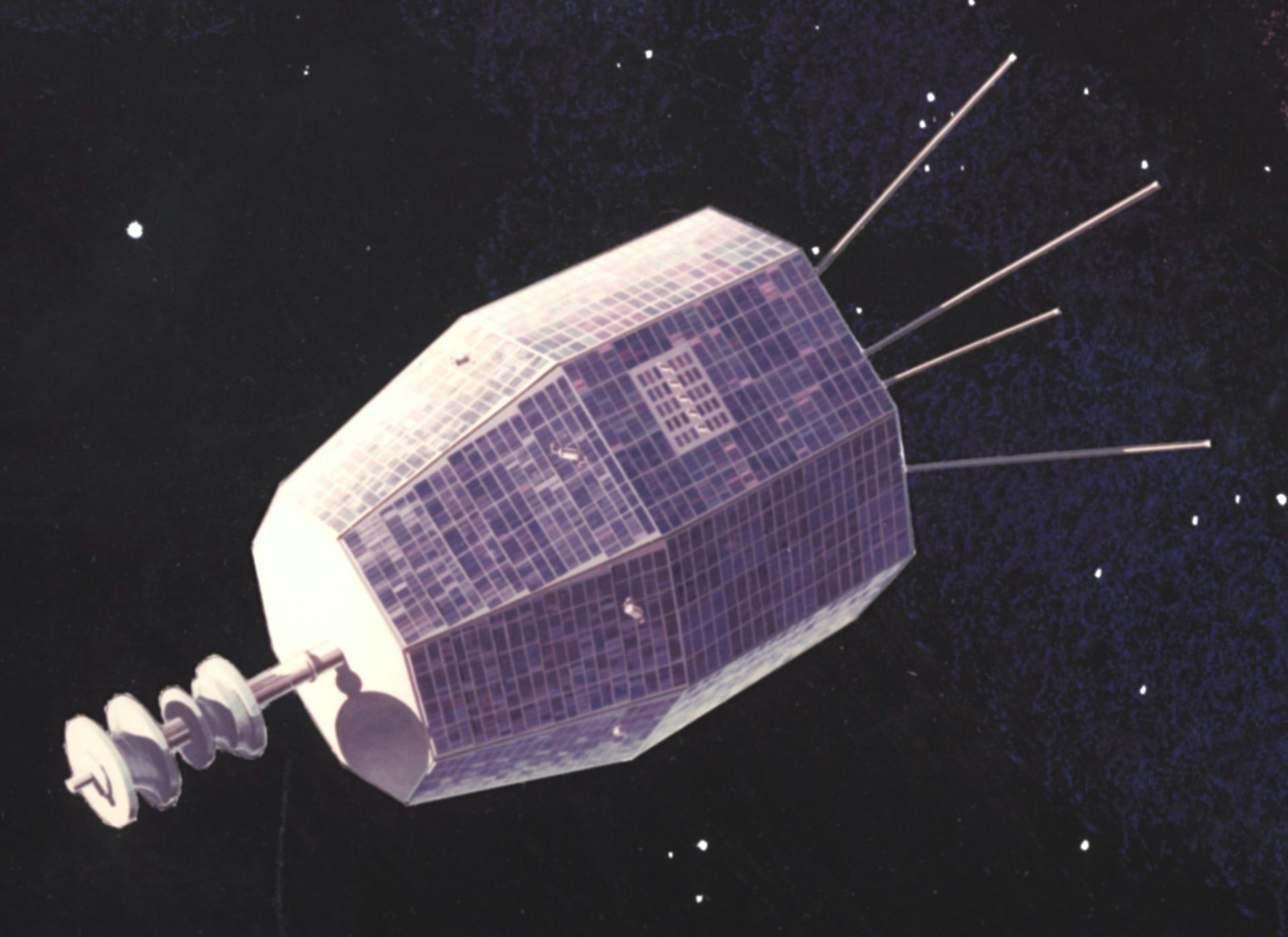

We already knew the route it got here from, and we had been ready to make use of the blurriness within the picture to estimate a distance of 4,500 km. And there was just one factor in that route, at that distance, at the moment — a derelict 60-year-old satellite tv for pc known as Relay 2.

Relay 2 was one of many first ever telecommunications satellites. Launched by the US in 1964, it was operated till 1965, and its onboard programs had failed by 1967.

However how might Relay 2 have produced this burst?

Some satellites, presumed useless, have been observed to reawaken. They’re referred to as “zombie satellites”.

However this was no zombie. No system on board Relay 2 had ever been in a position to produce a nanosecond burst of radio waves, even when it was alive.

We predict the most probably trigger was an “electrostatic discharge”. As satellites are uncovered to electrically charged gases in house referred to as plasmas, they will change into charged — just like when your feet rub on carpet. And that gathered cost can all of a sudden discharge, with the ensuing spark inflicting a flash of radio waves.

Electrostatic discharges are frequent, and are recognized to cause damage to spacecraft. But all recognized electrostatic discharges final 1000’s of occasions longer than our sign, and happen mostly when the Earth’s magnetosphere is very lively. And our magnetosphere was unusually quiet on the time of the sign.

One other chance is a strike by a micrometeoroid — a tiny piece of house particles — much like that experienced by the James Webb Space Telescope in June 2022.

In response to our calculations, a 22 micro-gram micrometeoroid travelling at 20km per second or extra and hitting Relay 2 would have been in a position to produce such a robust flash of radio waves. However we estimate the possibility the nanosecond burst we detected was attributable to such an occasion to be about 1%.

A lot extra sparks within the sky

Finally, we are able to’t make certain why we noticed this sign from Relay 2. What we do know, nevertheless, is the way to see extra of them. When 13.8 millisecond timescales — the equal of protecting the digital camera shutter open for longer — this sign was washed out, and barely detectable even to a strong radio telescope akin to ASKAP.

But when we had searched at 13.8 nanoseconds, any previous radio antenna would have simply seen it. It exhibits us that monitoring satellites for electrostatic discharges with ground-based radio antennas is feasible. And with the number of satellites in orbit growing rapidly, discovering new methods to observe them is extra vital than ever.

However did our crew ultimately discover new astronomical alerts? You bet we did. And there are little question loads extra to be discovered.

![]()

Clancy William James is a senior lecturer in astronomy and astroparticle physics at Curtin College. He receives funding from the Australian Analysis Council.

Curtin University supplies funding as a member of The Dialog AU.

This text is republished from The Conversation underneath a Inventive Commons license. Learn the original article.