Astronomers have found 53 new supermassive black hole-powered quasars which are blasting out jets of matter at close to light-speed that stretch out for as much as 7.2 million light-years, round 50 instances the width of the Milky Method.

These monster objects, generally known as Large Radio Quasars, are a part of a clutch of 369 radio quasars not too long ago found by Indian astronomers in knowledge collected by the Large Meterwave Radio Telescope (GMRT), an array of 30 parabolic dishes situated close to Pune, India, as a part of the TIFR GMRT Sky Survey (TGSS). The TGSS coated round 90% of the celestial sphere above Earth, with the telescope’s wide-sky protection and excessive sensitivity making it the perfect instrument to identify distant gigantic radio-emitting constructions like Large Radio Quasars.

To power a quasar, a supermassive black hole must be surrounded by a wealth of gas and dust, which it can feed on. This matter swirls around supermassive black holes in flattened cloud structures called accretion disks. The tremendous gravitational influence of supermassive black holes generates powerful tidal forces in accretion disks, heating this material, causing it to brightly emit radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum.

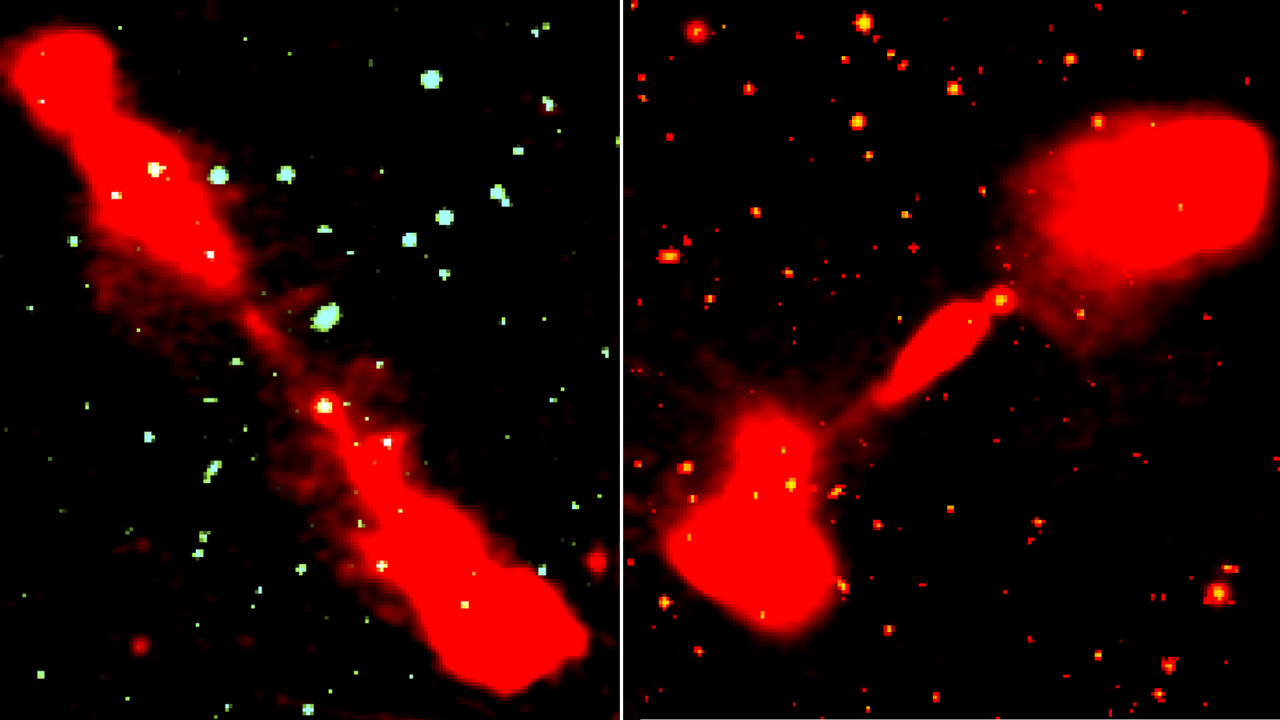

However, black holes are notoriously messy eaters, and not all of the matter in accretion disks is fed to them. Strong magnetic fields channel highly ionized gas, or plasma, to the poles of the supermassive black hole, where it is accelerated to near-light speeds and blasted out in opposing directions as powerful twin jets. Over time, and as they reach distances of many light-years away from their source, these jets can spread out into wide plumes or “lobes” fanning out far above and below the plane of the galaxy they emerge from. The jets and lobes are accompanied by strong radio wave emissions.

“Their enormous radio jets make these quasars valuable for understanding both the late stages of their evolution and the intergalactic medium in which they expand, the tenuous gas that confines their radio lobes millions of light-years from the central black hole,” team leader Sabyasachi Pal, an astronomer at Midnapore City College, said. “However, finding such giants is not easy.”The researcher explained that this is because the faint “bridge” of emissions that connects the two lobes often fades below detection limits, thus making the overall structure appear broken or incomplete.

“Low-frequency radio surveys are particularly effective for identifying these systems because the aged synchrotron plasma in the lobes emits more strongly at lower radio frequencies than at higher ones,” Pal continued.

The team noticed an interesting trend regarding Giant Radio Quasars and the environments in which they reside, finding that around at least 14% of these monstrous objects sit within galaxy groupings and clusters and near cosmic filaments of gas, dust and dark matter where galaxies gather and grow.

“It appears that the environment plays a major role in shaping how these radio jets evolve,” team member Netai Bhukta of Sidho Kanho Birsha University in Lagda, India, said in the statement. “In denser regions, the jets might be slowed down, bent, or disrupted by the surrounding gas, while in emptier regions, they can grow freely across the intergalactic medium.”

Though most quasars feature twin jets, the scientists noticed these jets are frequently uneven in terms of length or brightness, a disparity called radio jet asymmetry. “This asymmetry tells us that these jets are battling against an uneven cosmic environment,” team member Sushanta K. Mondal, also of Sidho Kanho Birsha University, said. “On one side, the jet may be ploughing into denser clouds of intergalactic gas, slowing its growth, while the other side expands freely through a thinner medium.”

The team’s findings seem to indicate that giant quasars at greater distances seem to display greater jet asymmetry compared to those closer to the Milky Way. This could be because the further away these quasars are, the further back in time we are seeing them, and the early cosmos was far more chaotic and packed with denser gas that distorted the paths of these jets.

The team’s research was published on Nov. 13 in The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series of the American Astronomical Society.