The highly effective thermonuclear explosions on the surfaces of two white dwarfs have been resolved intimately for the primary time, revealing that these eruptions are extra complicated than beforehand thought.

The findings are courtesy of the Heart for Excessive Angular Decision Astronomy (CHARA) array, which is an optical interferometer that mixes the sunshine of six telescopes on Mount Wilson in California. CHARA focused two occasions of this type, which astronomers name nova eruptions.

From Earth, we see a nova eruption as a brilliant brightening of the star, often to naked-eye visibility, hence why the sixteenth century astronomer Tycho Brahe christened this type of object a “nova,” which is Latin for “new star.”

Previously, astronomers had been unable to observe a nova as anything but a point-source of light, and had assumed that a nova was a single eruption of matter from one point on the white dwarf’s surface. However, the Fermi Space Telescope has in the past detected puzzling high-energy gamma-ray emissions from a host of nova eruptions, which implies there’s more going on than meets the eye.

Astronomers used CHARA in 2021 to target two nova eruptions within days of them brightening, namely nova V1674 Herculis and nova V1405 Cassiopeia.

“The images give us a close-up view of how material is ejected away from the star during the explosion,” Gail Schaefer of Georgia State University and Director of the CHARA array, said in a statement.

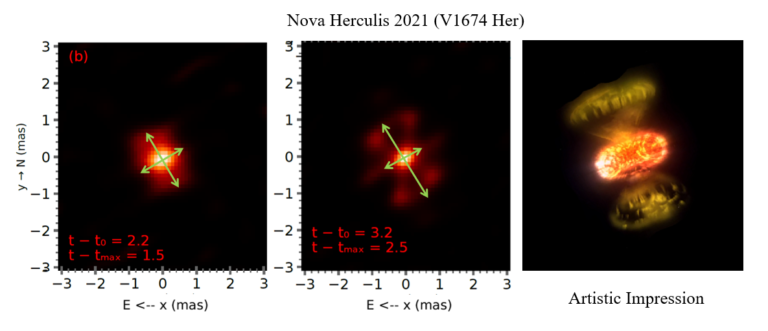

Both were very different from each other. V1674 Herculis experienced one of the fastest nova eruptions on record, brightening to magnitude 6 and fading in a matter of days. CHARA detected two bipolar outflows perpendicular to each other, rather than a global eruption all across the white dwarf’s surface. At the same time, the Fermi Space Telescope detected gamma rays from shocks as multiple components in the outflows violently collided.

Nova V1405 Cassiopeiae was, by comparison, a rather sluggish eruption with delayed outflows. CHARA showed that it took fifty days after the initial brightening for material to be lifted off the surface of the white dwarf at the center of the eruption. When the matter was finally ejected, it sparked new shocks as the outflows collided, also emitted gamma rays, and brightened to magnitude 5.5, making it just visible to the unaided eye from the darkest of observing sites. Its brightness stayed more or less the same for seven months before fading.

Additional information also came from the Multi-Object Spectrograph on the 8.1-meter Gemini North Telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. It tracked the matter ejected by the two nova eruptions through the spectral fingerprints of their chemical composition, such as ionized iron, showing how features in the spectrum of each nova aligned with outflow structures seen by CHARA.

“By seeing how and when the material is ejected, we can finally connect the dots between the nuclear reactions on the star’s surface, the geometry of the ejected material and the high-energy radiation we detect from space,” said Laura Chomiuk of Michigan State University.

The findings were published on Dec. 5 in the journal Nature Astronomy.