Earth is surrounded by human-made particles that orbits our planet. The issue is worsening yearly, and 2025 was no completely different.

House particles consultants say almost 130 million items of orbital junk are zipping round our planet: high-speed leftovers from rocket stage explosions, deserted satellites, in addition to bits and items of junk from house {hardware} deployments. A few of this meandering mess is the results of the deliberate demolition of spacecraft by means of anti-satellite weapons testing.

All this house litter means elevated danger of collisions that generate extra particles — higher often called the Kessler syndrome. That cascading effect was detailed back in 1978 by NASA scientists, Donald Kessler and Burton Cour-Palais in the seminal space physics paper “Collision frequency of artificial satellites: The creation of a debris belt.” 47 years later, the problem has only gotten worse, and as several debris strike incidents this year show, we still have no good way to solve or even slow down the accumulation of orbital debris around our planet.

Debris strike prompts emergency launch

As China’s Shenzhou-20 astronauts were preparing to undock from the country’s space station on Nov. 5, that crew found that their spacecraft had developed tiny cracks in its viewport window. The cause was tagged to an external impact from space debris, rendering the craft unsuitable for a safe crew return.

This incident called for the first emergency launch mission in China’s human spaceflight program; an uncrewed, cargo-loaded Shenzhou-22 spaceship was launched on Nov. 25.

The Shenzhou saga ended well with the Chinese astronauts safely returning to Earth aboard the Shenzhou-21 spacecraft. It was the first alternative return procedure activated in the history of China’s space station program.

However, the Shenzhou-20 landing delay is not just a procedural footnote. It’s a signal about the state of our orbital commons, said Moriba Jah, a space debris expert and professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

“A crew return was postponed because microscopic debris compromised a spacecraft window,” Jah told Space.com. “That decision, to delay and substitute vehicles, reflects responsible risk management grounded in incomplete knowledge. It also exposes the deeper issue. That is, our collective inability to maintain continuous, verifiable understanding of what moves through orbit,” he said.

Every fragment we leave aloft, said Jah, “adds to a rising tide of uncertainty.”

Wanted: data fidelity and transparency

That uncertainty is not merely statistical, it is epistemic, Jah said. “When the rate at which uncertainty grows exceeds the rate at which knowledge is renewed, safety margins erode,” advocating the designing of missions, governance frameworks, and information systems that “regenerate knowledge faster than it decays,” he said.

A cracked window of the Shenzhou-20 spacecraft, Jah said, “traces back to gaps in global tracking, attribution, and accountability. Until nations and companies treat data fidelity and transparency as part of safety engineering, similar near-misses will recur.”

China’s decision to delay the Shenzhou-piloted vessel’s re-entry until its engineers were confident in the assessment “was an act of epistemic humility — recognizing what was unknown and adjusting accordingly. Such humility should be codified, not exceptional,” he said.

In practice, Jah said that the Shenzhou-20 episode should push the international community toward auditable stewardship, that is, common baselines for orbital situational awareness, interoperable knowledge graphs, and certification programs that recognize missions restoring order rather than adding risk.

“Only by aligning engineering, policy, and information ethics can we prevent ‘routine’ anomalies from becoming precursors to catastrophe,” Jah said. “If we learn the right lesson, this will not be remembered as a lucky escape but as a turning point,” he said, adding that “evidence that safety in orbit begins with honesty about what we do and do not know, and with the will to regenerate knowledge faster than we lose it.”

Ignoring long-term effects

Darren McKnight is a senior technical fellow of LeoLabs, a group dedicated to space domain awareness.

For McKnight the biggest issues in 2025 were:

- Proliferation of satellite constellations, some responsibly like Starlink, Iridium, and OneWeb and some poorly like China’s “Thousand Sails” megaconstellation and its “Guowang” satellite internet payloads, leaving rocket bodies at a high rate and at high altitudes and not working with other constellations to “show your work, share your work, and understand context.”

- Abandonment of rocket bodies in orbits that will linger for more than 25 years. The good news is there can be a 30% reduction in debris-generating potential in low Earth orbit by removing the top 10 statistically-most-concerning objects. The bad news, however, is that the global community is leaving rocket bodies at an accelerating rate despite the known negative, long-term effects for doing so.

“Some operators in low Earth orbit are ignoring known long-term effects of behavior for short-term gain,” McKnight said, a situation he senses that parallels the early stages of global warming.

“Some will not change behavior until something bad happens.” McKnight concluded.

Risks and responsibilities

Raising another voice of concern is the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). This month it released “Safeguarding Space: Environmental Issues, Risks and Responsibilities.” That doc dubbed a set of house particles woes as “rising points.”

“The space sector is growing exponentially, with over 12,000 spacecraft deployed in the past decade and many more planned as the world embraces the benefits provided by satellite services. This growth presents significant environmental challenges at all layers of the atmosphere,” the document explains.

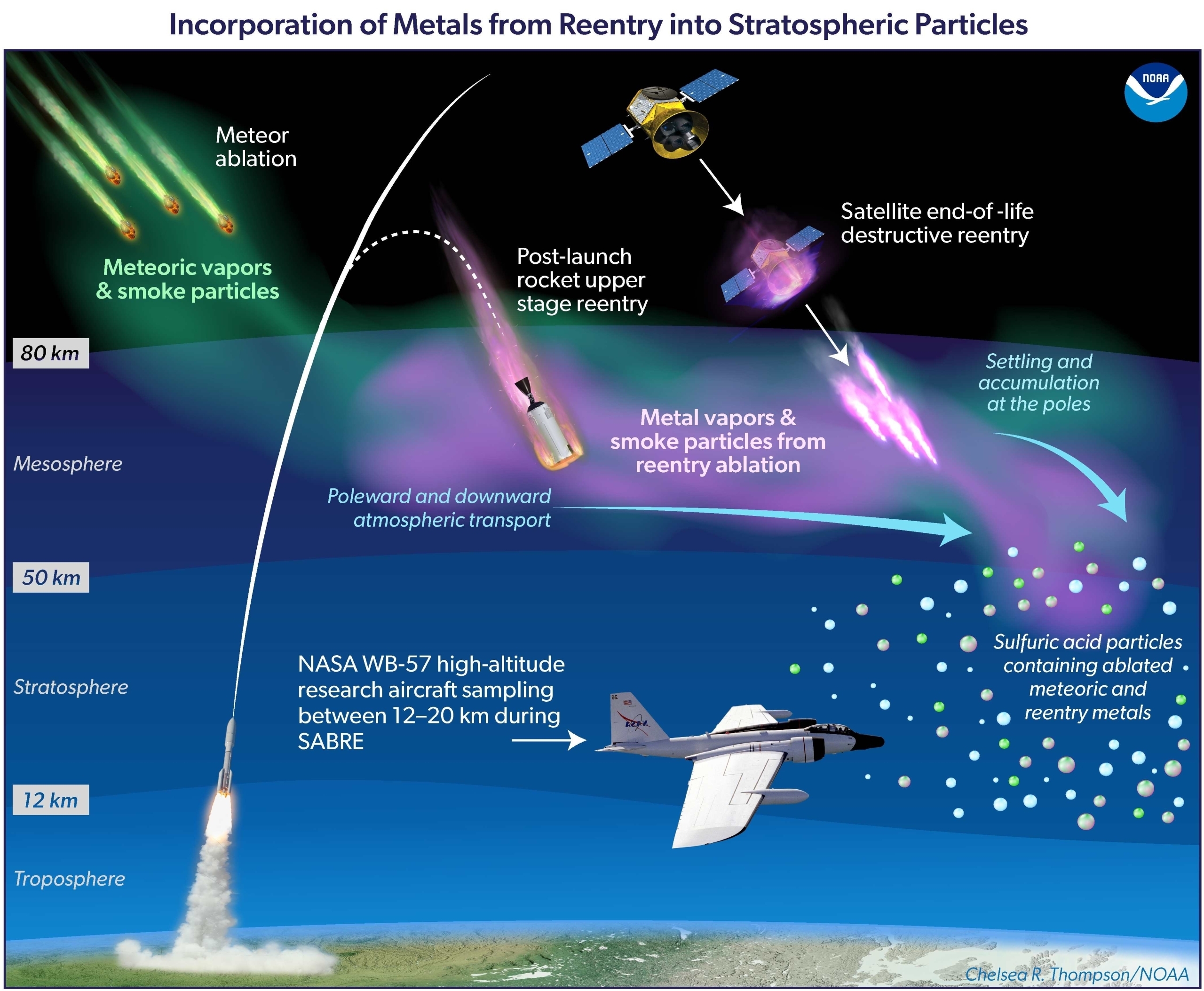

Specifically flagged by the UNEP are air pollution from launch emissions, spacecraft emissions in the stratosphere, as well as space debris re-entry and the potential to alter Earth’s atmospheric chemistry and dynamics with implications for climate change and depleting stratospheric ozone.

The UN group’s bottom line?

“A multilateral, interdisciplinary approach is needed to better understand the risks and impacts and how to balance them with the essential daily services and benefits that space activity brings to humanity,” the document states.