Europa may not be the perfect place to search for alien life within the photo voltaic system in spite of everything.

A brand new examine modeling what the ground of the Jupiter moon’s hidden ocean is like concluded that tectonic exercise — and the complicated chemical reactions that such exercise facilitates — might be negligible.

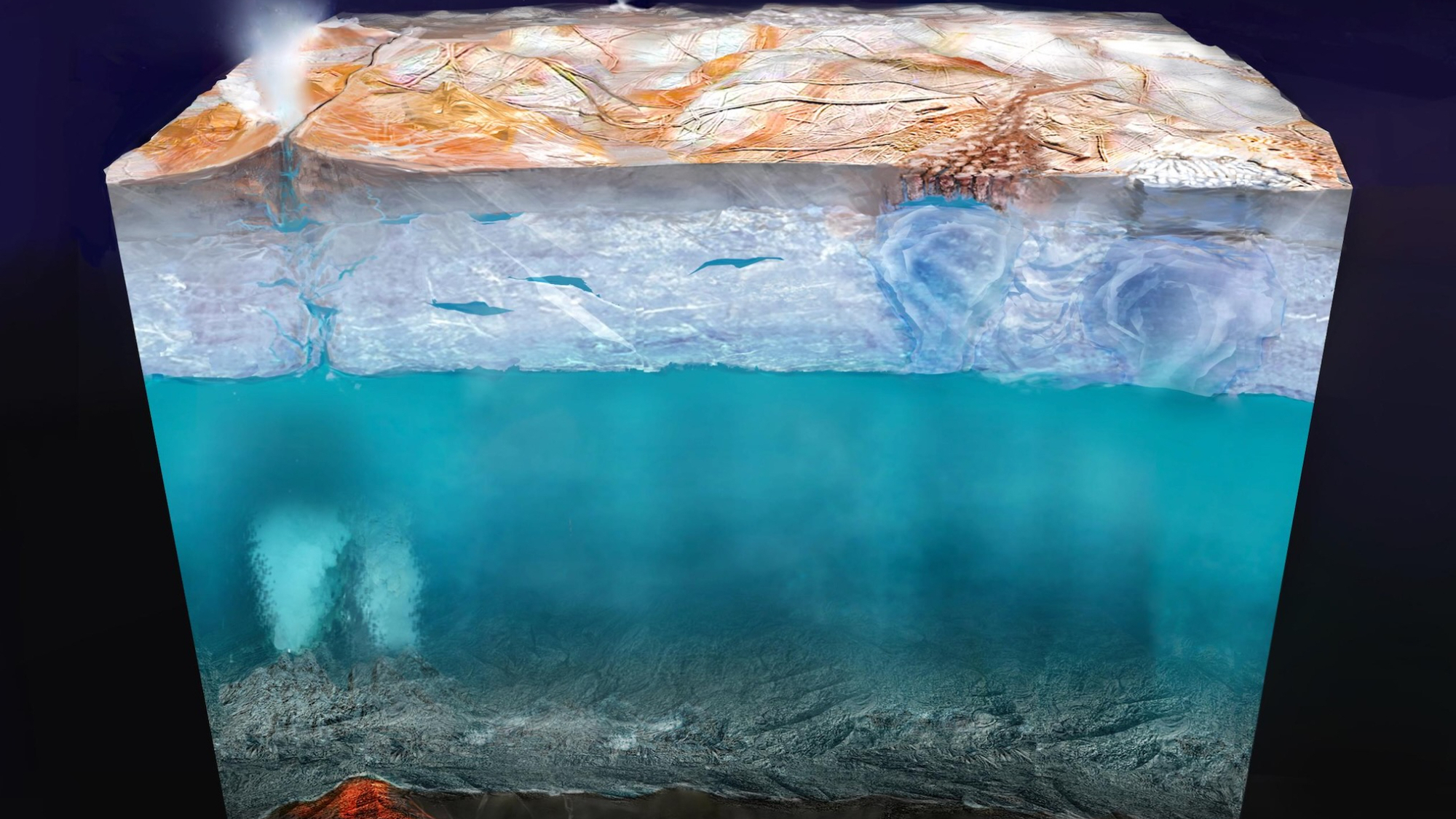

Europa harbors a deep ocean beneath a shell of ice that is dozens of kilometers thick. This ocean wraps round a rocky core, however little is understood concerning the interface between the ocean and the core. If life is to exist in Europa’s ocean, it should one way or the other acquire vitality, most likely from interactions on the sea ground between water and rock. Entry to recent rock is important with a view to produce extra vitamins.

On Earth, tectonic faulting within the seafloor permits water to plunge kilometers down into the rock, and as recent faults are opened up by shifting tectonic plates, new rock is uncovered, sustaining the nutrient provide launched into the ocean by hydrothermal vents.

Byrne’s team assessed the potential for tectonic activity on Europa’s seafloor with a new model that factored in stresses from gravitational tides incurred by Jupiter, the long-term contraction of the moon as its interior gradually cools and the convection of heat energy through the mantle.

However, they found that none of these factors would be strong enough to produce tectonic activity. For example, tidal stresses occur because Europa’s orbit around Jupiter is not perfectly circular but rather eccentric, in accordance with Johannes Kepler‘s first law of orbital motion. This means that, at certain points in each of its 84-hour orbits around Jupiter, Europa is closer to the planet than at other times, and the resulting gravitational differential leads to tides. However, for the tides to be strong enough to induce sufficient tectonic activity, the eccentricity of Europa’s orbit would have to be greater — more elongated — than it is (an eccentricity of 0.441 compared to the actual value of 0.009). Even if repeated tidal stresses weaken the uppermost part of Europa’s seafloor, creating shallow fractures, they aren’t intense enough to extend those faults deep down to new rock.

Similarly, while theoretical models suggest that Europa’s rocky core has contracted over billions of years as its interior has cooled, it would have to shrink several kilometers to fracture the bedrock and create deep tectonic faults. This would be more extensive than the process on Earth’s moon, which is estimated to have contracted by several tens of meters throughout its four-and-a-half billion-year history, though less than on Mars, which is thought to have contracted by up to 7 kilometers (4.3 miles).

The lack of tectonics is bad news for the possibility of life, since life would need fresh chemical nutrients to survive. One of the main sources of these nutrients on the floor of Earth’s oceans is hydrothermal vents, like the famous black smokers. But according to the new modeling, black smokers that billow out hot water filled with nutrients are not possible on Europa.

“But it turns out that there are other kinds of hydrothermal systems,” said Byrne. These other kinds percolate through the bedrock to shallower depths and hence are cooler.

“In fact, these other kinds are the most common on Earth,” Byrne added. “Such relatively cooler hydrothermal vents could exist on Europa, but they’d be far less energetic than the traditional images we have in our heads when we think about hydrothermal vents. And it’s very far from certain how long such cooler hydrothermal systems might last and support chemosynthetic microbial life.”

If hydrothermal vents and tectonic faulting are off the menu for Europa, are there any other possible sources of chemical energy and nutrients that could sustain life on the ocean moon? Maybe, said Byrne, but there are still too many unknowns to know for sure. For example, radioactive decay could be a substitute source of energy, but we don’t know the numbers for this process on Europa. Alternatively, perhaps nutrients enter the ocean not from below, but from above — meteorites that strike the surface ice and become subsumed and drawn into the ocean. However, it’s not clear whether there are routes through the thick ice shell into the ocean and vice versa. This is one of the unknowns that NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, currently on its way to Europa, aims to discover.

The findings are also potentially bad news for other ocean moons in the solar system, and Byrne’s team is currently preparing a new study that investigates this further.

“Without giving too much away, I can say that the overall findings for Europa are applicable to most other such moons, with the likely exception of [Saturn‘s moon] Enceladus,” Byrne said.

However, despite the pessimistic outlook, Byrne is keen to emphasize that we shouldn’t stop looking for life on these icy moons with their hidden oceans.

“We’re not saying, and we can’t say, that there’s no life in Europa,” said Byrne. “What we’re saying is that it’s a harder proposition, based on our results.”

The findings were published on Jan. 6 in the journal Nature Communications.