One of many least-mapped planetary surfaces in our photo voltaic system is nearer to house than you may anticipate: the continent of Antarctica.

Whereas Antarctica‘s icy floor is pretty well-studied, its subglacial bedrock panorama — situated as much as 3 miles (4.8 km) beneath the ice — is harder to discern. Present strategies of mapping require costly ground-based and airborne surveys, and such actions are few and much between.

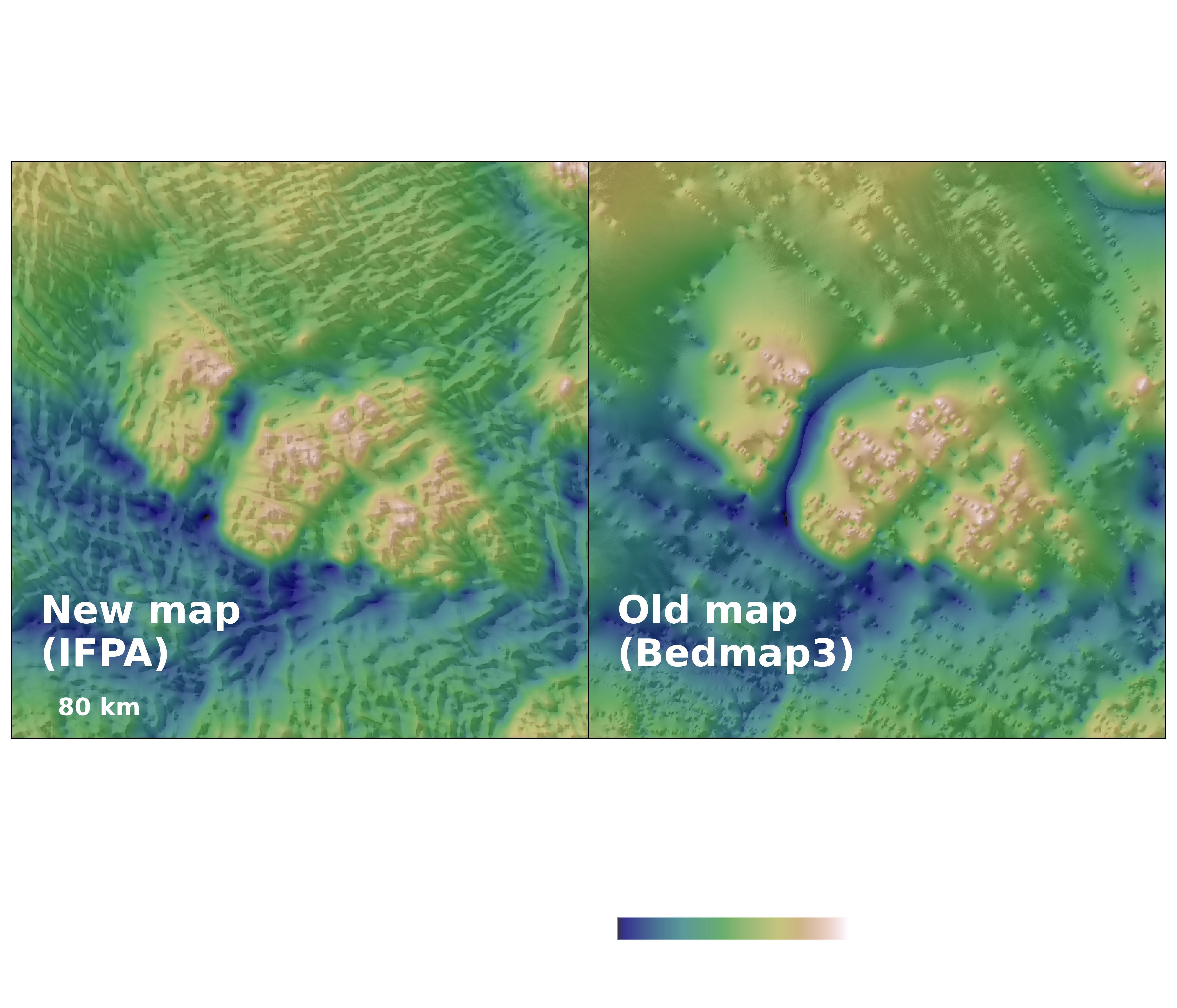

“Our IFPA map of Antarctica’s subglacial landscape reveals that an enormous level of detail about the subglacial topography of Antarctica can be inverted from satellite observations of the ice surface, especially when combined with ice thickness observations from geophysical surveys,” wrote the team in a new paper on their research.

In creating the map, the researchers discovered previously unknown or poorly resolved geologic features, from steep-sided channels possibly linked to mountain drainage systems to deep valleys reminiscent of U-shaped glacial valleys elsewhere on Earth. These features might provide insight to an ancient, pre-glacial Antarctica.

Maps like these are key to understanding the movement of the ice above across the continent, which ultimately allows researchers to predict how Antarctic ice might contribute to global sea-level rise.

But while this new IFPA map reveals unprecedented details about Antarctica’s hidden topography, there is still room for greater precision. The reconstruction resolves features at the mesoscale — about 1.2 to 18.6 miles (2 to 30 km) — meaning that smaller landforms remain beyond its reach.

“Our landscape classification and topographic map therefore serve as important guides toward more focused studies of Antarctica’s subglacial landscape, informing where future detailed geophysical surveys should be targeted, as well as the extents and resolutions (e.g., flight-track spacing) required to capture the fine details required for ice flow modeling,” the team wrote.

And there’s no better time than the present to prepare those future surveys. “The upcoming International Polar Year 2031-2033 presents a timely opportunity for international efforts to integrate expansive observation and modeling approaches to better understand ice sheet and bedrock properties, guided by methods similar to that of Ockenden et al,” Duncan Young, of the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, wrote in a “Perspective” piece accompanying the new study.

The team’s research was published in the journal Science on Jan. 15.