On the subject of greenhouse fuel emissions, carbon dioxide will get the lion’s share of world consideration.

However methane is the second-largest contributor to human-caused world warming. A excessive proportion of methane emissions comes from the vitality sector, usually from concentrated “level sources” resembling flare stacks, coal vents and open-pit mines. To assist scale back these emissions, we should first establish the foremost culprits — and new satellite tv for pc information helps us do exactly that.

“This is the first global gridded estimate of annual methane emissions from facility-scale measurements, an advancement in measurement-based accounting that is due to the comprehensive scale of GHGSat’s satellite constellation to measure methane worldwide,” said Dylan Jervis of GHGSat Inc., lead author of a new study on the findings printed Dec. 11 within the journal Science.

“This data will probably be helpful to enhance understanding and predictions of methane emissions, and, due to this fact, present data that’s helpful to direct mitigation efforts,” Jervis instructed Area.com.

Historically, scientists have measured methane emissions with a mixture of bottom-up inventories, which estimate emissions based mostly on trade exercise however can miss short-term fluctuations like leaks, and top-down atmospheric measurements, which detect methane concentrations straight however lack the decision to pinpoint particular sources. Neither can paint a really exact image of world methane emissions from the vitality sector. However the GHGSat constellation, run by the Canadian firm GHGSat, bridges that hole by combining meter-scale spatial decision with world protection.

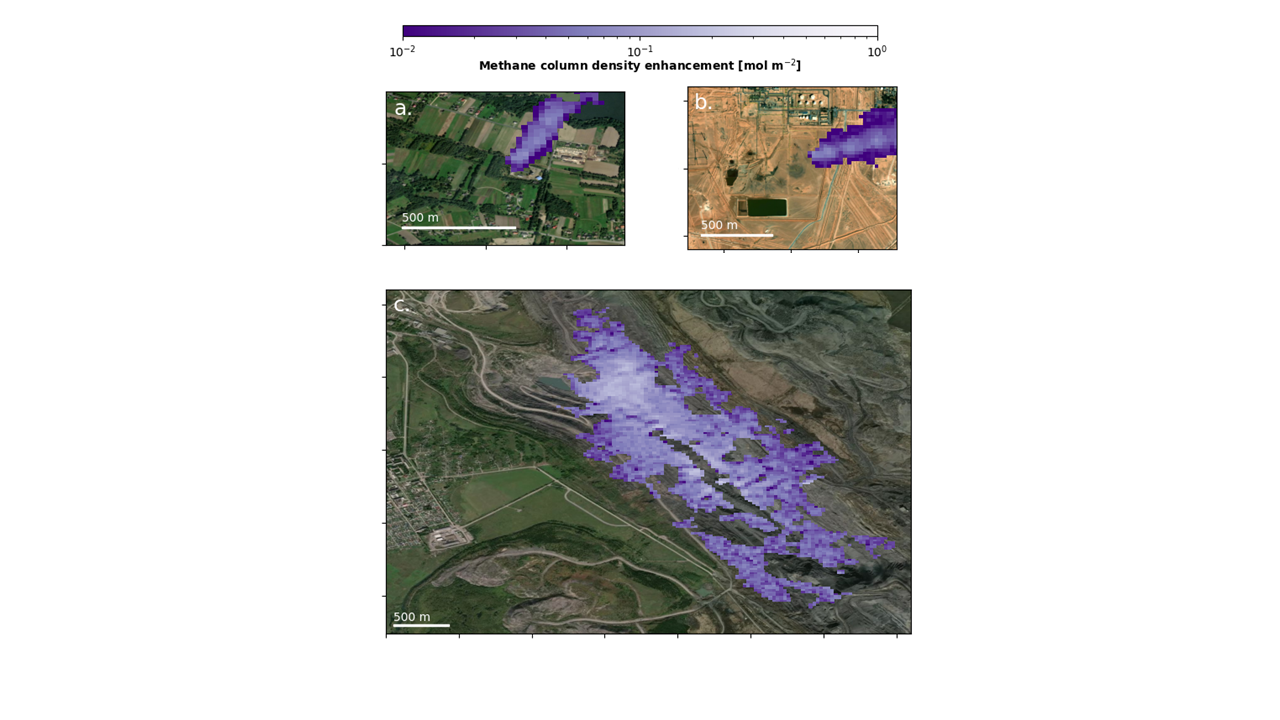

Analyzing GHGSat observations of methane plumes collected in 2023, the group estimated annual methane emissions from 3,114 oil, fuel and coal amenities worldwide that totaled about 9 million tons (8.3 million metric tons) per yr.

Geographically, the biggest emitters stood out clearly in the satellite data. “The countries where we measure the largest oil and gas methane emissions are Turkmenistan, the U.S., Russia, Mexico and Kazakhstan,” said Jervis. “The countries where we measure the large coal emissions are China and Russia.”

While bottom-up inventories are fairly good at estimating methane emissions on such large scales as countries, they aren’t nearly as precise when you zoom in. “We found moderate agreement between GHGSat-measured emission estimates and bottom-up inventory predictions at the country level, but very little agreement at 0.2 degree x 0.2 degree [about 20 by 20 kilometers] spatial resolution,” Jervis said. Thus, effective change may need to happen at the facility level, not at the country level.

The researchers tracked how often individual facilities emitted detectable methane plumes, a metric they call persistence.

“Persistence of emissions depends more on sector than region,” said Jervis. For coal facilities, methane plumes were detected about half the time on average. Oil and gas sites, by contrast, were far more intermittent, emitting detectable methane in only about 16% of satellite observations on average. That variability makes oil and gas emissions especially difficult to capture with infrequent monitoring.

For the most accurate and actionable methane estimates, detailed surveys like the ones provided by GHGSat are crucial — which is why GHGSat is growing its constellation. Two new satellites were launched in June, and two more in November, bringing the company’s total to 14 satellites. “This will enable better coverage, both spatially and temporally, allowing us to detect more emissions and monitor them more frequently,” said Jervis.