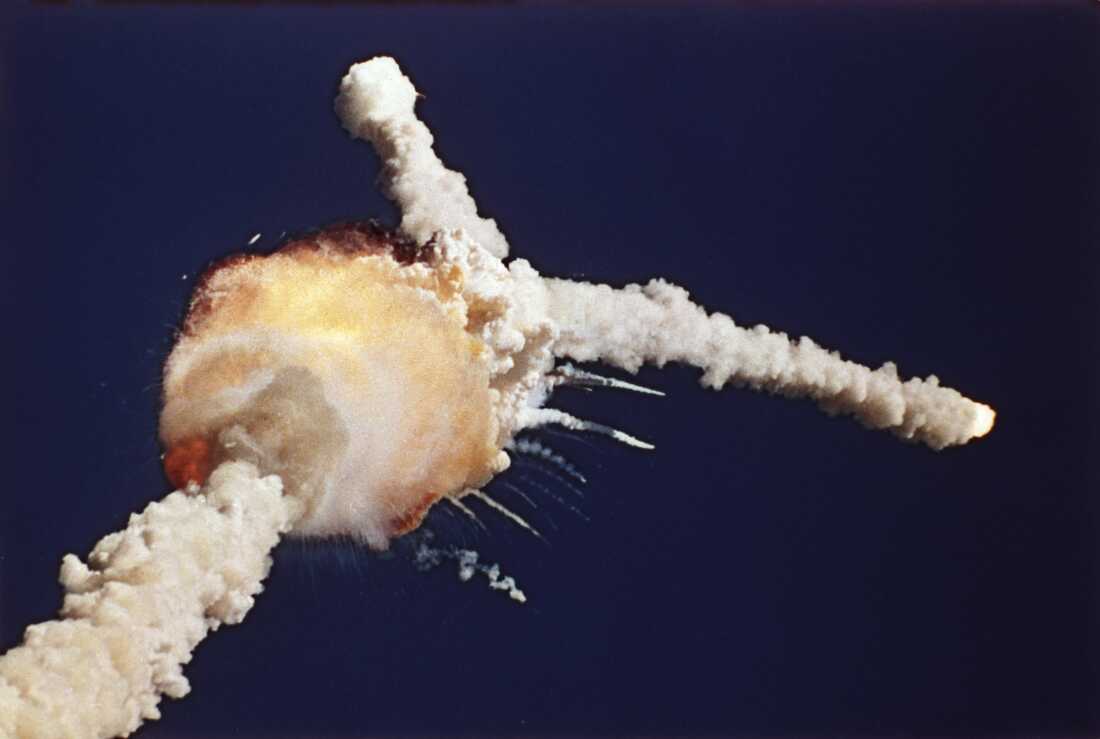

The area shuttle Challenger lifts off from Kennedy Area Middle in Florida on Jan. 28, 1986, in a cloud of smoke with a crew of seven aboard. The shuttle exploded shortly after this photograph.

Thom Baur/AP

conceal caption

toggle caption

Thom Baur/AP

Bob Ebeling was anxious and indignant as he drove to work on the morning of Jan. 28, 1986. He saved interested by the area shuttle Challenger, cradled on a Florida launchpad 2,000 miles away. Ebeling knew that ice had fashioned there in a single day and that freezing temperatures that morning made it too dangerous for liftoff.

“He mentioned we’re going to have a catastrophic occasion at this time,” recalled his daughter Leslie Ebeling, who, like her father, labored at NASA contractor Morton Thiokol and who was within the automotive in 1986 on that 30-mile drive to the corporate’s booster rocket advanced outdoors Brigham Metropolis, Utah.

“He mentioned the Challenger’s going to explode. Everybody’s going to die. And he was beating his palms on the dashboard. … He was frantic.”

Bob Ebeling at his residence in Brigham Metropolis, Utah, in 2016.

Howard Berkes/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Howard Berkes/NPR

The evening earlier than, Ebeling and different Morton Thiokol engineers tried to persuade NASA, the Nationwide Aeronautics and Area Administration, that launching in chilly climate could possibly be disastrous. The Thiokol engineers had information, paperwork and images that they believed offered convincing proof of the dangers. And Thiokol executives agreed, at first. Their official advice to NASA: Don’t launch tomorrow.

What occurred subsequent is a narrative now 40 years outdated. Nevertheless it consists of vital classes for the area program which might be nonetheless related at this time. It has additionally been a lingering supply of guilt for a number of the Thiokol engineers who “fought like hell to cease that launch.”

“A disaster of the very best order”

A problem with Morton Thiokol’s booster rocket design emerged in the course of the second shuttle flight in 1981. After that Columbia mission, and after Thiokol’s reusable booster rockets had been retrieved from their ocean splashdown, an inspection by firm engineers confirmed proof of “blow-by” in a rocket joint.

The rockets were built in segments, like tin cans stacked on high of one another. The place one section joined one other, two rows of artificial rubber O-rings had been supposed to maintain extraordinarily risky rocket gasoline from leaking out. Liftoff and early flight exerted monumental strain on the rockets, inflicting the joints to twist aside barely. The O-rings had been supposed to maintain these joints sealed. However on that second shuttle flight, searing-hot rocket gasoline and gases burned previous that interior O-ring barrier in a phenomenon generally known as blow-by.

5 years and two dozen shuttle missions later, Morton Thiokol had a particular job pressure working full time on O-ring blow-by. One engineer on that job pressure, Roger Boisjoly, wrote a memo six months before the Challenger disaster that warned of “a disaster of the very best order — lack of human life” if the O-ring drawback wasn’t mounted.

Shuttles continued to launch regardless of the continued threat. Some blame that on one thing referred to as the “normalization of deviance,” an idea coined by sociologist Diane Vaughan in 1996 after she studied the Challenger catastrophe. Vaughan concluded that even after the danger was recognized and even whereas it was the main focus of concern and research, shuttle flights continued as a result of the danger hadn’t but induced a catastrophe. The “deviance” of the O-ring blow-by turned normalized.

A trainer instructing from area

The crew of the area shuttle Challenger. Entrance row from left are Michael Smith, Dick Scobee and Ronald McNair. Again row from left are Ellison Onizuka, Christa McAuliffe, Gregory Jarvis and Judith Resnik.

NASA by way of AP

conceal caption

toggle caption

NASA by way of AP

5 days earlier than Challenger’s 1986 launch, the shuttle’s crew of seven arrived at Kennedy Area Middle in Florida, pausing on the tarmac earlier than a gaggle of microphones. Commander Dick Scobee spoke first, adopted by pilot Michael Smith, mission specialists Judith Resnik, Ellison Onizuka and Ronald McNair, and payload specialist Gregory Jarvis. The seventh crew member was Christa McAuliffe, a highschool trainer from New Hampshire.

“Nicely, I’m so excited to be right here,” McAuliffe mentioned, smiling broadly. “I do not suppose any trainer has ever been extra able to have two classes. … And I simply hope everyone tunes in on Day 4 now to observe the trainer instructing in area.”

McAuliffe’s participation was attracting extra consideration than normal to shuttle flights on the time. Earlier than this Challenger mission, shuttle launches had been so routine that the three main broadcast tv networks stopped protecting launches dwell. NASA determined that placing a “trainer in area” aboard would increase curiosity.

It labored, to a degree. The printed TV networks did not carry the launch dwell, however lecturers in lecture rooms throughout the U.S. rolled out TV units so hundreds of thousands of schoolchildren might watch dwell feeds from CNN or NASA. Busloads of scholars had been additionally within the crowd at Kennedy Area Middle, together with the households of some astronauts.

“It is time to … put in your administration hat”

Bob Ebeling and different firm engineers had been watching on the Morton Thiokol booster rocket advanced in Utah. They crowded right into a convention room with Thiokol managers and executives; all centered on a big projection TV display screen.

The evening earlier than, in the identical convention room, Ebeling and his colleagues had tried to persuade NASA booster rocket program managers phoning in from the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama that the chilly climate made launching dangerous. The artificial rubber O-rings lining the booster rocket joints stiffened in chilly temperatures, and this could be the coldest launch ever by far. The Thiokol engineers feared blow-by would burn by means of each units of O-rings, triggering an explosion at liftoff.

At first, Thiokol’s engineers and executives formally really helpful a launch delay. However the NASA officers on the road pushed again onerous. The launch had already been delayed 5 instances. The NASA officers mentioned the engineers could not show the O-rings would fail. A kind of engineers, wanting again on it now, 40 years later, says it was an unachievable burden of proof.

“It is unattainable to show that it is unsafe. Primarily, you must present that it will fail,” explains Brian Russell, who was a program supervisor at Morton Thiokol in 1986 and who was centered on the O-rings and booster rocket joints.

Brian Russell appears to be like at notes from the Challenger mission.

Howard Berkes for NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Howard Berkes for NPR

“What we had been saying was we’re rising the danger considerably,” Russell remembers. However “you simply cannot” show the O-rings will fail, he provides. “So, we had been in an absolute lose scenario.”

NASA’s resistance in the course of the contentious, generally argumentative convention name ultimately wore down the 4 Thiokol executives within the Utah convention room. They and the NASA officers on the road additionally heard one piece of knowledge that fed their resistance. O-ring blow-by had additionally occurred throughout a heat launch: 75 levels.

“So, it wasn’t simply as simple as saying, ‘Hey, we had been on a rock-solid basis with no opposing information.’ We weren’t,” Russell remembers. Russell additionally says the info confirmed that harm at colder temperatures was much more extreme and alarming.

Thiokol had so much at stake with this Challenger launch. The corporate’s contract with NASA imposed a $10 million penalty for a launch delay as a result of booster rockets. That contract was value $800 million, and it was up for renewal in 1986.

The Thiokol executives put NASA on maintain so they might converse privately with their engineers. Russell, Ebeling, Boisjoly and one other engineer within the room had been insistent. It was too dangerous to launch, they mentioned. Lastly, Thiokol Senior Vice President Jerry Mason polled the corporate executives. He and two others rapidly agreed to reverse their earlier advice and approve the launch. Mason then turned to Bob Lund, the vp in command of engineering.

“And Bob hesitated and hummed and hawed, and I might inform it was such a troublesome choice for him, and it was all hinging on him,” Russell remembers. “He was representing each administration in addition to engineering … and in his hesitation, Jerry Mason mentioned, ‘Bob, it is time to take off your engineering hat and put in your administration hat.'”

And that is exactly what Lund did. He placed on his administration hat and voted to overrule his engineers. Challenger’s destiny was set.

A serious malfunction

The following morning, NASA’s dwell feed displaying launch preparations included this announcement from the launch management workforce: “I’ve polled the technical neighborhood, and you’ve got our consensus to proceed with this launch. Good luck and Godspeed.”

Brian Russell, Bob Ebeling and Roger Boisjoly knew that wasn’t true. They had been a part of the “technical neighborhood,” they usually by no means backed down from their advice to delay. However the launch director and different high NASA officers did not comprehend it. All they knew was what the lower-level officers on the Marshall Area Flight Middle instructed them: Thiokol and its rockets had been “go” for launch. On the time, that is all that was anticipated. The Marshall Area Flight Middle supervised Thiokol’s booster rockets, and the Marshall officers merely instructed the launch management workforce that the boosters had been prepared.

Leslie Ebeling watched the launch together with her dad and the opposite engineers within the Thiokol convention room. The elder Ebeling and some others anticipated a disastrous explosion at ignition. So when Challenger lifted off and cleared the launch tower, there was some aid. However not for Bob Ebeling.

“My dad bent down to inform me that it wasn’t over but, that issues weren’t clear. And I might really feel him trembling,” recalled Leslie Ebeling. Then launch management introduced, “Challenger, go together with throttle up.”

All of a sudden, there was a second of static on the audio feed, together with billowing smoke and flames within the video, in addition to items of the spacecraft taking pictures wildly throughout the sky. “Clearly a significant malfunction,” mentioned a voice on the NASA feed.

The area shuttle Challenger explodes shortly after lifting off from Kennedy Area Middle in Florida on Jan. 28, 1986. The explosion was blamed on defective O-rings within the shuttle’s booster rockets.

Bruce Weaver/AP

conceal caption

toggle caption

Bruce Weaver/AP

“After which he wept, loudly,” Leslie Ebeling mentioned of her dad’s response. “And the silence in that room was deafening. There was nobody speaking. It was simply useless silence.”

Within the crowd at Kennedy Area Middle, a TV digicam and microphone captured screams and sobbing, and the faces of Christa McAuliffe’s dad and mom as they regarded skyward in anguish. A loudspeaker with the NASA feed confirmed the worst: “We now have a report relayed by means of the Flight Dynamics Workplace that the automobile has exploded.”

That evening, CBS Information anchor Dan Somewhat referred to as it “the worst catastrophe within the U.S. area program ever.”

“Tonight, the seek for survivors turned up none,” Somewhat continued. “The seek for solutions is simply beginning.”

“I fought like hell to cease that launch”

A particular presidential commission started investigating per week after the tragedy however initially didn’t get the total story from NASA witnesses. On the first public hearing, on Feb. 6, Judson Lovingood, a shuttle supervisor at NASA’s Marshall Area Flight Middle, offered a truncated description of the convention name with Thiokol.

“We had the undertaking managers from each Marshall and Thiokol within the dialogue,” Lovingood testified. “We had the chief engineers from each locations within the dialogue. And Thiokol really helpful to proceed within the launch.”

Lovingood added that there was some concern concerning the chilly temperatures within the forecast, however that is all he mentioned. There was no point out of the objections of the Thiokol engineers, so the fee moved on.

4 days later, in a hearing behind closed doors, Lawrence Mulloy, one other high official at Marshall, mentioned, “All of us concluded that there was no drawback with the anticipated temperatures.”

However this time, one of many Thiokol engineers was within the room.

“I used to be sitting there considering, ‘Nicely, I suppose that is true, however that is about as deceiving as something I ever heard,'” recalled Allan McDonald in a 2016 interview. He was the rapid supervisor of the Thiokol engineers.

Allan McDonald, who was a direct supervisor of Morton Thiokol engineers, in 2016 holds a commemorative poster honoring the seven astronauts killed aboard the area shuttle Challenger.

Howard Berkes/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Howard Berkes/NPR

McDonald was sitting at the back of the room, in what he referred to as a budget seats, and unable to restrain himself, he spoke up.

“I feel this presidential fee ought to know that Morton Thiokol was so involved, we really helpful not launching beneath 53 levels Fahrenheit, and we put that in writing and despatched that to NASA,” McDonald remembers saying.

“I will always remember Chairman William Rogers and his vice chairman, Neil Armstrong, standing up and squinting and taking a look at me, and Chairman Rogers mentioned, ‘Would you please come down right here on the ground and repeat what I feel I heard?'”

The forecast for in a single day temperatures for the Challenger launch ranged from 18 to 26 levels Fahrenheit. The air temperature was nonetheless solely 36 levels after a two-hour launch delay.

4 days later, in one other closed-door listening to, the fee heard the first formal testimony from Thiokol engineers. McDonald instructed the fee that Thiokol was pressured by NASA to approve the launch. Roger Boisjoly, who led the eleventh-hour effort to delay the launch, testified concerning the O-ring job pressure, together with his warning of a disaster six months earlier than.

Little of this testimony was public. Bits of closed-door testimony leaked, however not the dramatic particulars of the decision-making course of that didn’t heed dire warnings of a catastrophe. These particulars had been lastly revealed on Feb. 20, 1986, in a pair of tales for NPR’s Morning Version, reported by my colleague Daniel Zwerdling and me.

We managed to get two Thiokol engineers to offer a play-by-play account of the convention name the evening earlier than the launch, together with direct quotes. Each engineers remained nameless on the time. They feared for his or her jobs, they usually’d been ordered by Thiokol to not speak publicly concerning the incident. Additionally they declined to be recorded. However they allowed us to report what they mentioned. A long time later, NPR was permitted to publicly establish them each.

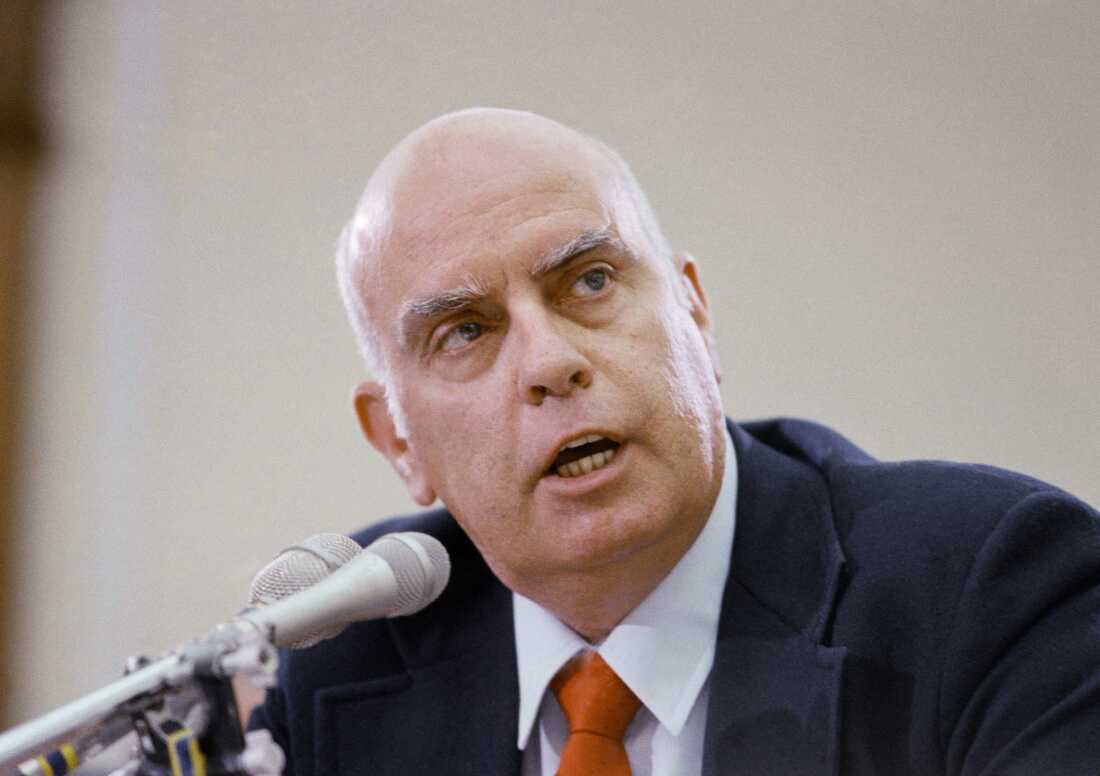

Morton Thiokol engineer Roger Boisjoly — showing earlier than the Home Committee on Science and Expertise on June 17, 1986 — particulars the objections he needed to the launch of area shuttle Challenger when he realized of freezing temperatures at Kennedy Area Middle.

John Duricka/AP

conceal caption

toggle caption

John Duricka/AP

“I fought like hell to cease that launch,” a tearful Boisjoly instructed Zwerdling in a lodge room close to the Marshall Area Flight Middle in Huntsville, Ala., on Feb. 19, three weeks after the explosion. “I am so torn up inside I can hardly discuss it, even now.”

“I ought to have achieved extra”

On the similar time, 1,700 miles away in Brigham Metropolis, Utah, Bob Ebeling spoke with me. He was nonetheless frantic, pacing forwards and backwards between his kitchen and front room, shaking his head and wringing his palms.

Each Ebeling and Boisjoly offered an identical tales about that convention name.

When the Thiokol engineers argued that NASA ought to anticipate hotter climate, Marshall’s Lawrence Mulloy blurted out, based on Ebeling, “My God, Thiokol, when would you like me to launch, subsequent April?”

NASA was making an attempt to show the area shuttle might fly on an everyday and dependable schedule, and in each month of the yr, regardless of chilly climate. Mulloy later told the Challenger commission that he did not consider he was making use of strain that evening earlier than the launch.

“Any time that one in every of my contractors … who come to me with a advice and a conclusion that’s based mostly on engineering information, I probe the idea for his or her conclusion to guarantee that it’s sound and that it’s logical,” Mulloy testified.

However Mulloy’s remark, which he didn’t deny making, proved pivotal. It preceded the choice of the Thiokol executives to overrule their engineers.

Ebeling instructed me that he noticed within the native newspaper a photograph of graffiti on a railroad overpass that mentioned, “Morton Thiokol Murderers.” He then walked into the lounge, the place haunting photos of the Challenger explosion appeared in a TV information report.

“I ought to have achieved extra,” Ebeling then mentioned. “I might have achieved extra.”

Classes realized

The Challenger fee concluded it was “an accident rooted in history,” given the proof of O-ring harm earlier than the deadly launch and the failure to heed the warnings of the Thiokol engineers.

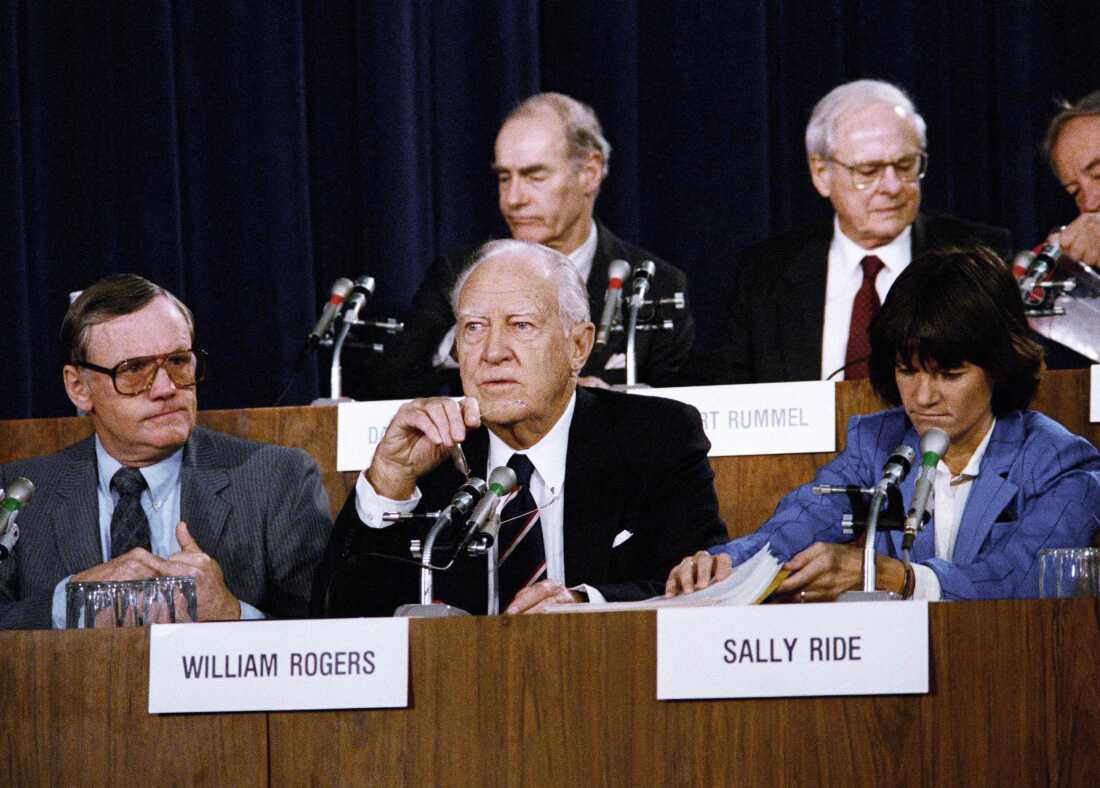

The fee additionally documented a stunning hole within the Challenger launch choice: the failure of the lower-level officers on the Marshall Area Flight Middle to inform the launch management workforce that there have been severe issues about launching. At a listening to on Feb. 27, Fee Chairman William Rogers posed a key query to the Challenger launch director, the Kennedy Area Middle director and two high shuttle program executives.

“Did any of you gents previous to launch know concerning the objections of Thiokol to the launch?” Rogers requested. Every of the 4 high NASA launch officers responded with a “No, sir” or “I didn’t.”

“Actually, 4 of the important thing individuals who made the choice concerning the launch weren’t conscious of the historical past we have been unfolding right here earlier than the fee,” Rogers concluded.

The chairman of the Presidential Fee on the Area Shuttle Challenger Accident, William Rogers (middle), and panel members Neil Armstrong (left) and Sally Experience attend one of many hearings regarding the catastrophe, on Feb. 25, 1986, in Washington, D.C.

Charles Tasnadi/AP

conceal caption

toggle caption

Charles Tasnadi/AP

NASA modified the launch choice course of after the Challenger catastrophe in order that objections of contractors would attain the launch management workforce.

However, nonetheless, 17 years later, after one other shuttle, Columbia, disintegrated throughout its Earth reentry, a NASA investigation blamed, partially, “organizational boundaries that prevented efficient communication of vital security data and stifled skilled variations of opinion.”

Columbia and Challenger prompted NASA, in addition to one of many Thiokol engineers, to systematically remind area company officers, staff and contractors about key classes from Challenger and different disasters.

The teachings from Challenger are vital for “the subsequent era of spaceflight,” mentioned Michael Ciannilli just lately, who retired from NASA after 36 years on the area company, together with in a key position in launch choices after Challenger. Ciannilli additionally developed and applied an “Apollo, Challenger, Columbia Classes Realized Program” at NASA, which has concerned hundreds of NASA staff and contractors.

“The oldsters within the organizations should really feel it is not simply platitudes or a pleasant slogan. However that is actually how it’s. … We honor dissenting opinion. We welcome dissenting opinion. There is no ramifications,” Ciannilli says.

He left NASA because the company shed 4,000 staff final yr, however he says he’ll proceed his “classes realized” work as a contractor.

NASA additionally invited me to talk about my reporting on Challenger to undertaking and security managers on the company’s Goddard Area Flight Middle and the Langley Analysis Middle in 2017. My assigned matter: “Listening to Dissent.”

Former Thiokol engineer Brian Russell has been taking an identical message to mission administration groups and different NASA officers on the Johnson Area Middle, Kennedy Area Middle, NASA headquarters and the Marshall Area Flight Middle (twice) — all since April 2025.

“The folks which might be concerned within the packages at this time face the identical points. They face the identical pressures on the subject of desirous to launch,” Russell explains.

“They will be beneath the strain to carry out, and nobody desires to be the one to face up and say, ‘I am not prepared,'” he continues. “However the listening beneath high-stress environments like that’s actually essential, and that is the crux of our message.”

“It’s a must to have an finish to all the things”

Nonetheless, Russell has some lingering remorse about his position within the effort to cease the Challenger launch. He remembers the second in 1986 when the Thiokol executives overruled the engineers, reconnected the convention name and instructed the NASA officers that Thiokol was “go” for launch.

“The factor that I really feel probably the most guilt over … [is] I want I might have mentioned, ‘There is a dissenting view right here.’ I want the [NASA] folks on the telephone name would’ve heard that,” Russell says, his eyes filling with tears. “However I nonetheless did not converse up. So, I remorse that … to at the present time.”

Roger Boisjoly instructed me in an interview in 1987 that he had no regrets. “There’s nothing I might have achieved additional as a result of you must understand we had been speaking to the fitting folks. … We had been speaking to the folks that had the ability to cease the launch.”

Boisjoly blamed Thiokol and NASA. He later turned a number one voice for moral decision-making within the engineering and management worlds. Boisjoly died in 2012.

Allan McDonald, the engineer who first spoke out throughout an early Challenger fee listening to, was initially demoted and sidelined by Thiokol. However members of Congress vowed to ensure the corporate would by no means obtain one other NASA contract if it punished McDonald and the opposite engineers for talking out. Thiokol relented, and McDonald was put in command of the profitable redesign of the booster rocket joints. “That turned out to be one of the best remedy on the planet,” he instructed me in 2016. McDonald died in 2021.

Bob Ebeling carried deep and painful guilt for 30 years. In 2016, he instructed me that placing him on that convention name with NASA the evening earlier than the launch was “one of many errors that God made.” It was one thing he prayed about.

Bob Ebeling along with his daughter Kathy Ebeling (middle) and his spouse, Darlene Ebeling, in 2016. All three have since handed away.

Howard Berkes/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Howard Berkes/NPR

“[God] should not have picked me for that job. … However subsequent time I speak to him, I am gonna ask him, ‘Why me? You picked a loser.'”

Ebeling was 89 then and had residence hospice care. He used parallel bars to stroll from his kitchen desk to his favourite simple chair in the lounge.

I reported his painful remorse in a narrative on the thirtieth anniversary of the Challenger catastrophe, and a whole bunch of NPR listeners responded, together with every kind of engineers. Most had comforting phrases. Two of the important thing individuals who had been concerned within the 1986 convention name, and who didn’t heed the warnings of the engineers, additionally responded, saying Ebeling offered information and paperwork. They instructed him that he did his job and was not the decision-maker, so he shouldn’t bear any blame.

NASA additionally responded with a press release, which I learn to Ebeling in February 2016: “We honor [the Challenger astronauts] not by means of bearing the burden of their loss however by continually reminding one another to stay vigilant and to hearken to these like Mr. Ebeling who’ve the braveness to talk up in order that our astronauts can safely perform their missions.”

Listening to that, Ebeling smiled, raised his palms above his head and clapped. “Bravo! I’ve had that thought many instances,” he mentioned.

“It’s a must to have an finish to all the things,” he added earlier than I left, as he clapped and smiled once more.

Bob Ebeling died three weeks later, at peace, his household mentioned.