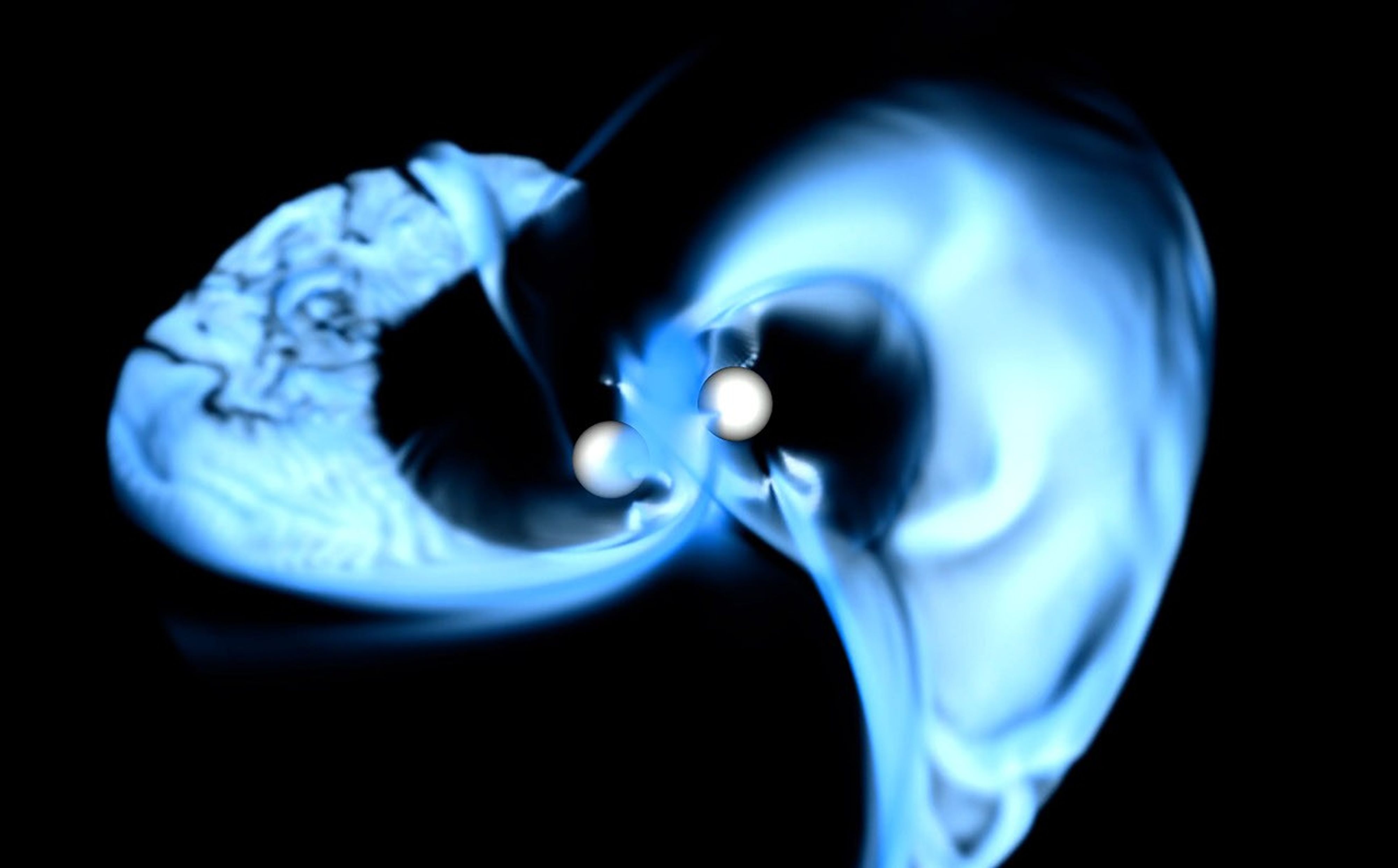

A brand new simulation created utilizing a NASA supercomputer has proven how issues get messy for merging neutron stars even earlier than they slam collectively; their magnetospheres, essentially the most highly effective magnetic fields within the recognized universe, entwine and generate chaos.

“Simply earlier than neutron stars crash, the extremely magnetized, plasma-filled areas round them, known as magnetospheres, begin to work together strongly,” group chief Dimitrios Skiathas, a researcher at NASA’s Goddard Flight Middle, mentioned in a press release. “We studied the final a number of orbits earlier than the merger, when the entwined magnetic fields endure fast and dramatic adjustments, and modeled probably observable high-energy alerts.”

What makes neutron stars so excessive?

When stars with across the identical mass because the solar run out of hydrogen, the gas mandatory for nuclear fusion in their cores, their cores collapse and their outer layers swell out and are eventually lost. This leads to the stars ending their lives as smoldering stellar embers called white dwarfs.

However, the situation is different for stars with around 10 times the mass of the sun and more. When their hydrogen-depleted cores collapse, the extra mass generates the pressure and temperatures needed to allow the helium, created in these cores over millions of years of hydrogen fusion, to fuse, forming even heavier elements.

This repeated process of fuel exhaustion, collapse and reignition continues until the massive star’s heart is filled with iron. When this final collapse happens, shockwaves ripple out to the star’s outer layers, which are blown away in a supernova explosion, taking with them the vast majority of the star’s mass.

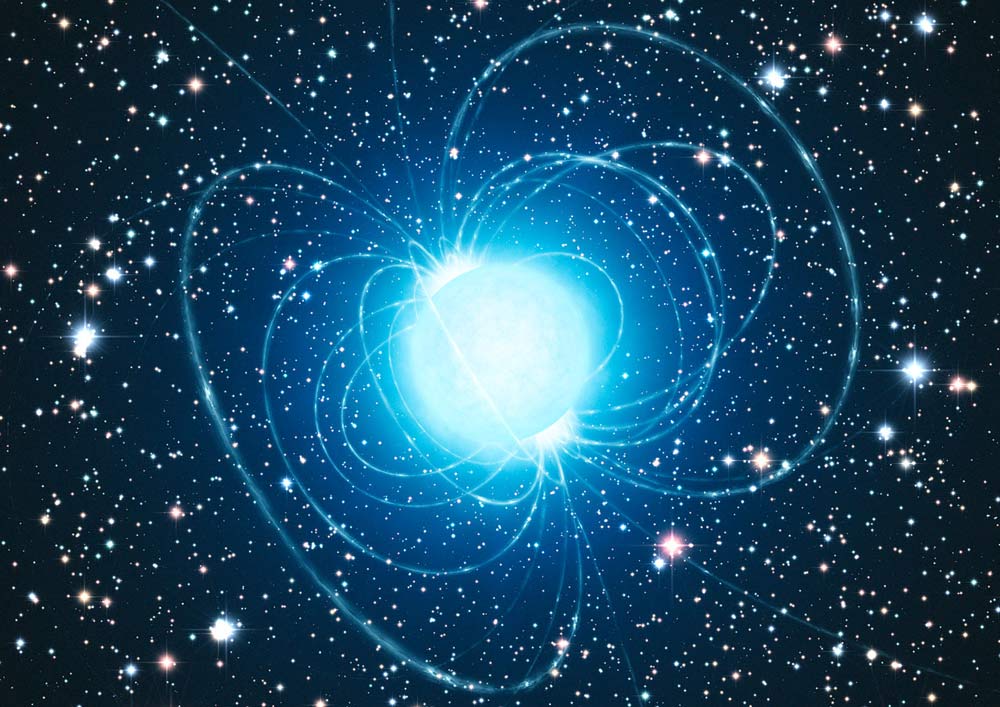

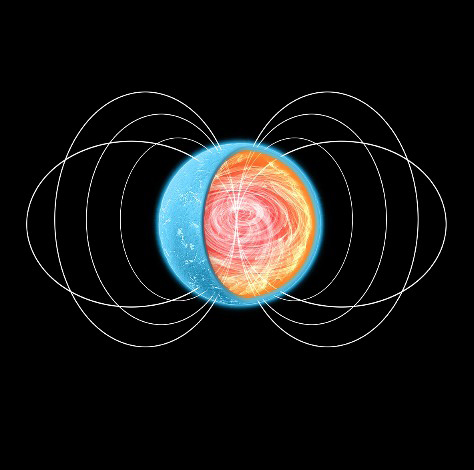

The result is a stellar remnant with a mass between one and two times the mass of the sun, filled with neutron-rich matter crammed into a width of around 12 miles (20 kilometers). The rapid crushing down of this stellar core doesn’t just create a body of incredible density, but also creates magnetic fields that can be 1 quadrillion times stronger than Earth’s magnetosphere.

Massive stars are often found in binary pairs with a stellar companion, and in these cases, when both stars die, a neutron star binary is the result. As the two dead stars swirl around each other, they generate ripples in spacetime called gravitational waves, which carry away angular momentum. This results in the neutron star binary tightening. In other words, the stellar remnants move closer, causing them to emit gravitational waves of higher frequencies, losing angular momentum more rapidly and drawing together even faster.

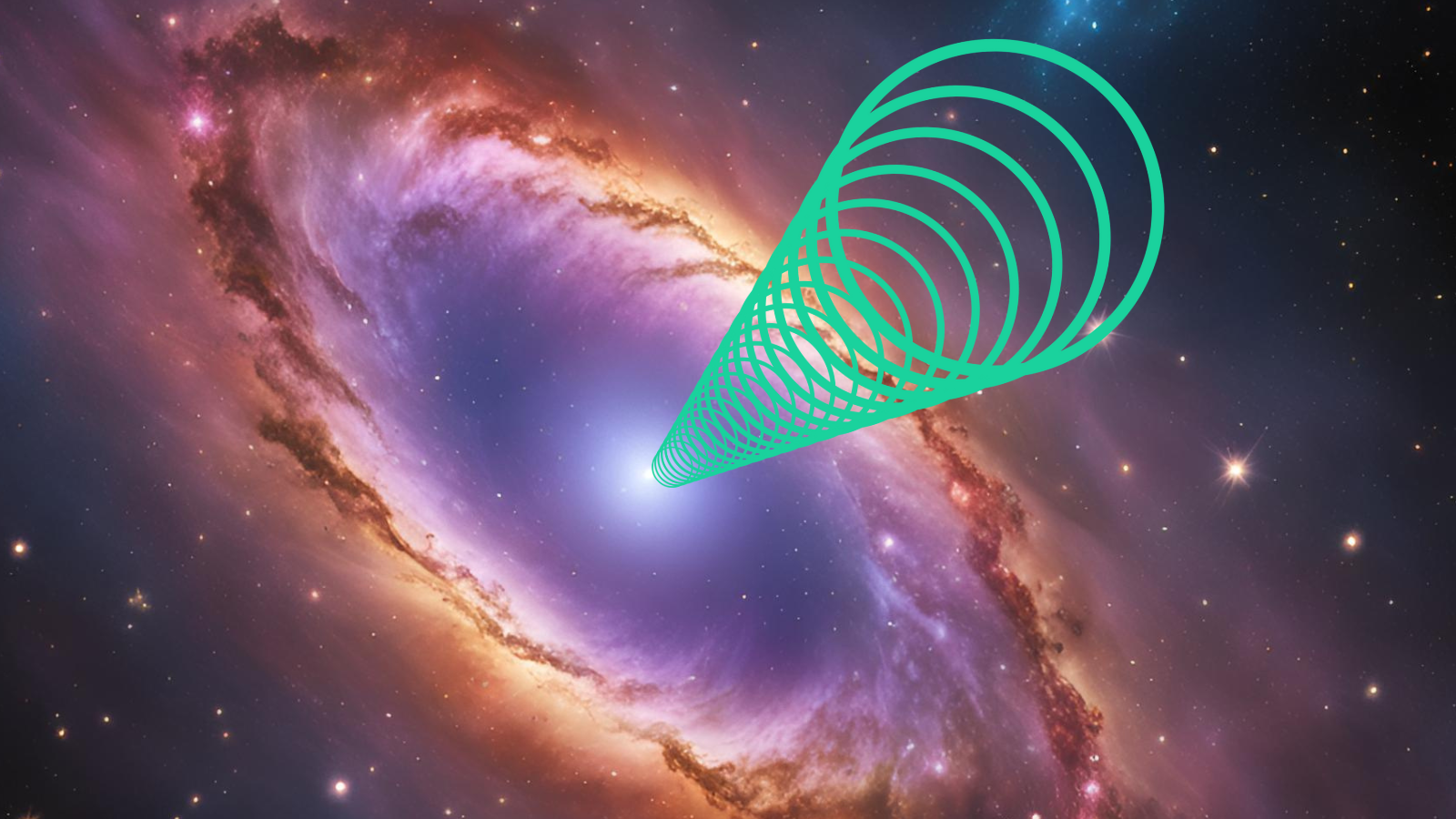

This ends when the neutron stars are close enough to each other for their gravity to take over, leading to an inevitable collision and merger. This causes a blast of high-energy radiation called a gamma-ray burst (GRB), a final screech of gravitational waves, and sends out a spray of neutron-rich matter, which allows a process to occur that generates very heavy but unstable elements. These eventually decay to create gold, silver, and other metals heavier than iron. The decay also creates a glow that astronomers call a kilonova.

The fact that these events are responsible for the creation of some of our most precious and important elements, as well as bright cosmic phenomena like GRBs and kilonovas, means there has been a heavy bias toward studying the aftereffects of neutron star mergers.

Skiathas and colleagues took a different approach, looking in more depth at what happens prior to the neutron stars meeting.

Messy magnetism

To consider the 7.7 milliseconds prior to neutron stars merging, the team turned to NASA’s Pleiades supercomputer at NASA’s Ames Research Center, creating over 100 simulations of a system of two neutron stars, each with around 1.4 times the mass of the sun.

“In our simulations, the magnetosphere behaves like a magnetic circuit that continually rewires itself as the stars orbit. Field lines connect, break, and reconnect while currents surge through plasma moving at nearly the speed of light, and the rapidly varying fields can accelerate particles,” team member Constantinos Kalapotharakos of NASA Goddard said in the statement. “Following that nonlinear evolution at high resolution is exactly why we need a supercomputer!”

The team’s main aim was to investigate how the magnetic fields of these stellar remnants impacted light, or electromagnetic radiation in technical terms, during the final orbits of the neutron stars around each other.

“Our work shows that the light emitted by these systems varies greatly in brightness and is not distributed evenly, so a far-away observer’s perspective on the merger matters a great deal,” team member Zorawar Wadiasingh of the University of Maryland, College Park, and NASA Goddard, added in the statement. “The signals also get much stronger as the stars get closer and closer in a way that depends on the relative magnetic orientations of the neutron stars.”

The simulations revealed that respective magnetic fields of the neutron stars swept out behind them as they orbited each other, connecting the stellar remnants, then breaking, then reconnecting once again.

The researchers were also able to use Pleiades to simulate how electromagnetic forces impacted the surfaces of the neutron stars. The aim of this was to determine how magnetic stress accumulates in such systems, but future modeling will be needed to determine how magnetic interplay plays a role in the final moments of a neutron star merger.

“Such behavior could be imprinted on gravitational wave signals that would be detectable in next-generation facilities,” team member and NASA Goddard researcher Demosthenes Kazanas said in the statement. “One value of studies like this is to help us figure out what future observatories might be able to see and should be looking for in both gravitational waves and light.”

The researchers were able to use the simulated magnetic fields to identify the points where the highest-energy emissions were created and how these emissions would propagate through the environment of the neutron star merger.

The researchers found that regions around neutron star mergers produce gamma-rays with high energy, but this radiation was unable to escape. That was because gamma-ray photons, individual particles of light, were rapidly transformed into pairs of electrons and positrons. However, lower-energy gamma-rays were able to escape the neutron star merger along with even lower-energy radiation like X-rays.

The NASA/European Space Agency project Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) could be particularly useful in this regard. Set to launch in the mid-2030s, LISA will be the first space-based gravitational wave detector, benefiting from a much greater sensitivity than the current generation of Earth-based detectors, including the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO).The team’s results were published on Nov. 20, 2025 in The Astrophysical Journal.