An extremely energetic “unimaginable” particle that hit Earth in 2023 might have been particles from an exploding primordial black gap fashioned in the course of the Massive Bang. If that’s the case, then it may show the existence of primordial black holes, which may then assist clarify what the universe’s most mysterious “stuff,” darkish matter, is made from.

The particle in query was a neutrino with an vitality 100,000 instances better than that of the highest-energy particles produced by the world’s largest and strongest particle accelerator, the Giant Hadron Collider (LHC). In reality, the particle was so energetic that scientists aren’t conscious of any pure cosmic phenomena highly effective sufficient to create it.

The key to black hole explosions is the leaking of Hawking radiation, a type of thermal radiation named for physicist Stephen Hawking, who first proposed its existence in 1974. The hotter a black hole is, the quicker it leaks Hawking radiation, losing mass and then finally ending its life in a massive explosion.

The catch is that the bigger a black hole is, the colder it is, and the more slowly it loses thermal radiation to its surroundings. Thus, even the smallest stellar mass black holes, born when massive stars go supernova at the end of their lives, would take about 10^67 years, vastly longer than the age of the universe, to leak enough radiation to reach this explosive stage.

However, Hawking also theorized that another type of black hole may exist, one born not from the death of a star but directly from density fluctuations in the “primordial sea” of ultrahot particles that filled the cosmos during its first moments after the Big Bang. And because these primordial black holes can be extremely small, with masses down to that of a planet or even a large asteroid rather than 3 to 5 times the mass of the sun, like the smallest stellar mass black holes, then they could be hot enough to leak Hawking radiation efficiently enough to explode.

“The lighter a black hole is, the hotter it should be and the more particles it will emit,” team member Andrea Thamm of the University of Massachusetts Amherst said in a statement. “As primordial black holes evaporate, they develop into ever lighter, and so hotter, emitting much more radiation in a runaway course of till explosion. It is that Hawking radiation that our telescopes can detect.”

The astronomers behind this analysis estimate {that a} primordial black gap ought to explode with a frequency of round one each ten years or so. To date, none of those explosions have been detected, and due to this fact, primordial black holes and Hawking radiation each stay purely theoretical. That’s, in fact, except proof of an exploding primordial black gap was found courtesy of a distinct kind of detection, the true nature of which wasn’t instantly grasped.

The unimaginable particle

The impossibly energetic neutrino was detected in 2023 by a community of neutrino detectors known as KM3NeT situated within the Mediterranean Sea.

“Observing the high-energy neutrino was an unimaginable occasion,” staff member and College of Massachusetts Amherst researcher Michael Baker stated. “It gave us a brand new window on the universe. However we may now be on the cusp of experimentally verifying Hawking radiation, acquiring proof for each primordial black holes and new particles past the Standard Model, and explaining the mystery of dark matter.”

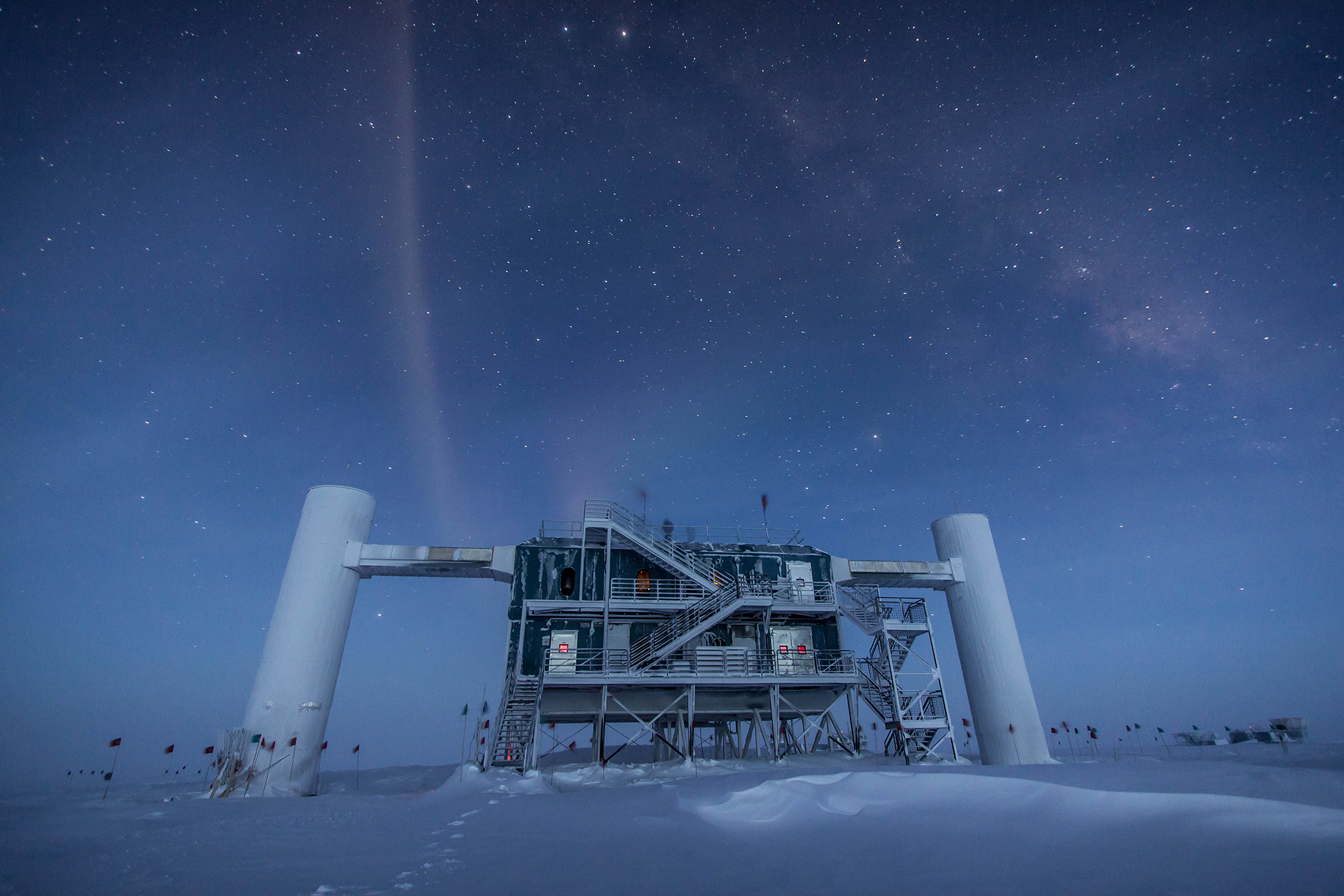

However, there is a hitch. The event wasn’t picked up by a similar neutrino detector called IceCube, situated deep within the ice of the South Pole. That was a problem, because IceCube was specifically designed to detect high-energy neutrinos, and yet it’s never detected one of these particles with even 1/100 of the energy of the impossible neutrino.

If a primordial black hole explodes once a decade, then IceCube should be bombarded with high-energy neutrinos. So where are they?

The University of Massachusetts Amherst team has a theory.

“We think that primordial black holes with a ‘dark charge’ — what we call quasi-extremal primordial black holes — are the missing link,” team member Joaquim Iguaz Juan of the University of Massachusetts Amherst said.

A “dark charge” is a version of the electromagnetic force that we are familiar with, but is carried not by a standard electron, but by a much heavier relative, a hypothetical particle called a “dark electron.”

“There are other, simpler models of primordial black holes out there,” Baker said. “Our dark-charge model is more complex, which means it may provide a more accurate model of reality. What’s so cool is to see that our model can explain this otherwise unexplainable phenomenon.”

A primordial black hole with a dark charge would have unique properties that make it behave differently from a standard primordial black hole, and that could not only explain the impossible neutrino but it could also solve the mystery of what dark matter actually is.

Dark matter has been so problematic because, unlike the particles that comprise standard matter, it doesn’t interact with electromagnetic radiation, or “light.” This means that despite outweighing ordinary particles by a ratio of 5 to 1, dark matter is effectively invisible and totally mysterious. One possible candidate for dark matter is primordial black holes.

“If our hypothesized dark charge is true, then we believe there could be a significant population of primordial black holes, which would be consistent with other astrophysical observations, and account for all the missing dark matter in the universe,” Iguaz Juan concluded.

The team’s research was accepted for publication in the journal Physical Review Letters.